This month we learned about the relationship between spiritual experience, psychosis, and transformation, as well as the neuroscience of consciousness, new science funding mechanisms, the effect of clocks on people’s sense of time, the evolution of pain, and the influence of scientists on nuclear weapons policy.

Pivotal mental states

by Ari Brouwer

There are striking similarities between transformative spiritual experiences that change people’s lives for the better, and those that lead to psychosis. The author has researched what they call “pivotal mental states” which they see as an evolved capability for sudden and radical psychic change.

Related: The academic article on which this is based: Pivotal mental states

The Scientists, the Statesmen, and the Bomb: A case study in decision-making around the development of powerful technologies

by Samo Burja and Zachary Lerangis

This case study looks at attempts by scientists to influence the development of nuclear weapons in the US. While the scientists often were able to gain access to key decision makers, they couldn’t influence them, and this was often the result of a culture class between scientists and decision makers. This case study is useful to inform current attempts to influence the development of new, potentially-dangerous technologies.

Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism

by E. P. Thompson

Historian E.P. Thompson traces how the spread of clocks and the development of industrial capitalism changed people’s conception of time. People in pre-industrial societies experienced time through the succession of tasks in a day, and had little demarcation between work time and the rest of life. But the synchronisation of labour required in factories led to a new “time-discipline” based on clock-time.

An evolutionary medicine perspective on pain and its disorders

by Randolph M. Nesse and Jay Schulkin

Evolutionary medicine can offer new perspectives for understanding chronic pain. This article suggests that chronic pain could be better understood through looking at signal detection in situations of uncertainty, the mismatch between modern environments and those from human history, and the relationship between psychic and physical pain.

Related: This article is part of a special issue on the evolution of mechanisms and behaviour important for pain.

So You Want To Run A Microgrants Program

by Scott Alexander

This article by psychiatrist and blogger Scott Alexander describes his experience of running a microgrants programme. He gives an unusually honest account of facing the uncertainty and responsibility of making grantmaking decisions.

Related: Scott Aaronson’s writeup of his microgrants programme.

Unblock research bottlenecks with non-profit start-ups

by Adam Marblestone, Anastasia Gamick, Tom Kalil, Cheryl Martin, Milan Cvitkovic, Samuel G. Rodriques

This article outlines the need for Focussed Research Organisations (FROs), which develop tools or datasets to accelerate research. These would be non-profit and would fill a gap not currently filled by academia or for-profit companies. They compare FROs to other types of organisation, outline the authors’ progress in setting new ones up, and discuss the challenges ahead.

Is Reality a Controlled Hallucination?

by Anil Seth

Neuroscientist Anil Seth outlines his work to explain how consciousness works, breaking it down into three aspects – the level of consciousness, the content of consciousness, and the experience of the self.

Related: Seth’s book Being You: A New Science of Consciousness

Thanks for reading!

We’re always looking for interesting reading materials so get in touch if you have any to share.

This month we’ve been particularly interested in the mind and brain – with articles on therapy methods, psychosomatic illness, and Alzheimer’s. We’ve also been reading articles following our interests in tools for thought, global catastrophic risks, and the workings of the philanthropic sector.

Curing Alzheimer’s by Investing in Aging Research

by Eli Dourado and Joanne Peng

The US Congress allocates billions of dollars each year to Alzheimer’s research but this isn’t paying off in successful treatments. The authors suggest that it would be better to fund fundamental research in the biology of ageing. This would lead to better approaches to Alzheimer’s and to other diseases of aging.

Related: The maddening saga of how an Alzheimer’s ‘cabal’ thwarted progress toward a cure for decades

How I Attained Persistent Self-Love, or, I Demand Deep Okayness For Everyone

by Sasha Chapin

The author describes his journey towards feeling a sense of persistent self-love he calls “Deep Okayness” which is “the total banishment of self-loathing”. As well as describing the methods he used, he argues that current thinking around mental health is too limited as it assumes that it isn’t possible to get to very high levels of persistent happiness. He also suggests that the tools used in mainstream mental health are not the most powerful tools we have available.

Related: The author’s other writing on his journey Stranded on the Space Mountains of Self-Loathing and Two Solo MDMA Trips Totally Ended My Self-Loathing.

A Primer on Memory Reconsolidation and its psychotherapeutic use as a core process of profound change

by Bruce Ecker, Robin Ticic and Laurel Hulley

Therapists face the challenge that their clients often have deep-rooted nonconscious emotional learnings that drive their suffering. This article describes a process that therapists can use to help clients unlearn these learnings, gives a case study example, and summarises the neuroscience research that underpins the method. They argue that these techniques can lead to a permanent cessation of people’s symptoms.

Related: Memory Reconsolidation: Key To Transformational Change in Psychotherapy – a talk which covers similar ideas to the article.

Götz Bachmann’s Ethnographic Research on Dynamicland

by Christoph Labacher

This post summarises the findings of ethnographer Götz Bachmann, who embedded himself with the secretive Dynamic Medium Group, run by engineer and designer Bret Victor. The research group has a vision of computing that seeks to build on the legacy of foundational computer research from Doug Englebart and Xerox Parc. It has developed a project called Dynamicland, which is a “communal computer” that you interact with through physical objects. Bachmann got to observe their internal dynamics, including their prototyping process and internal conflicts over strategy.

Related: The “Next Big Thing” is a Room, which describes Dynamicland.

‘You think I’m mad?’ – the truth about psychosomatic illness

by Suzanne O’Sullivan

This is an extract from O’Sullivan’s book on psychosomatic disorders, based on her experience as a neurologist. It describes three patients she saw with psychosomatic conditions – someone who went blind, someone who couldn’t open her hand, and someone who couldn’t walk. She describes how she diagnosed each of them and the process of treatment, including the challenges along the way.

How Nonprofits Helped Fuel the Opioid Crisis

by Jim Rendon

The article describes the links between pharmaceutical companies that make opioids and patients’ and physicians’ advocacy groups. It argues that pharmaceutical companies saw nonprofits as an important part of their strategy and that nonprofits funded by them downplayed the risks of opioids.

Related: Two articles on the consequences of the reaction to the opioid crisis for people with chronic pain: A Drug Addiction Risk Algorithm and Its Grim Toll on Chronic Pain Sufferers and The Unseen Victims of the Opioid Crisis Are Starting to Rebel.

Concrete Biosecurity Projects (some of which could be big)

by Andrew Snyder-Beattie and Ethan Alley

A list of projects that the authors see as critical parts of biosecurity infrastructure for reducing catastrophic biorisk. This includes an early detection centre, improved PPE, and strengthening the biological weapons convention.

Related: Two overview articles on biorisks by one of the authors: Human Agency and Global Catastrophic Biorisks and Existential Risk and Cost-Effective Biosecurity.

ACX Grants Results

by Scott Alexander

Blogger and psychiatrist Scott Alexander created a mini-grant scheme to give away $250,000 with a minimum of paperwork, using an effective altruist framework. Projects that got grants include: a campaign for approval voting in Seattle, creating software to automate parts of the FDA approval process, and work to develop a next-generation antiparasitic drug.

Related: Another blogger, computer scientist Scott Aaronson, announces a grants programme.

Thanks for reading!

We’re always looking for interesting reading materials so get in touch if you have any to share.

Unifying Theories of Psychedelic Drug Effects

by Link Swanson

This paper describes how scientists have explained the effects of psychedelic drugs over the course of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. The paper finds common ideas shared between all the theories, and looks at how they explain the diversity of subjective effects, healing power, and ability to mimic aspects of psychosis associated with psychedelic drugs.

A Drug Addiction Risk Algorithm and Its Grim Toll on Chronic Pain Sufferers

by Maia Szalavitz

This article reports on software used throughout the US to help doctors and pharmacists to evaluate the risk of addiction in patients. How this software calculates its risk scores is opaque, but it has significant influence over prescribing decisions and this can lead to patients being denied medication that is essential for them to manage their pain.

Related: The Unseen Victims of the Opioid Crisis Are Starting to Rebel.

I Am Not Your Baby Mother

by Candice Brathwaite

The author shares her personal account of becoming a mother in London as a Black British woman, including how she nearly died from postpartum sepsis and how she navigates racism and cultural expectations of motherhood. Her story is interspersed with national statistics about inequalities in maternal and neonatal healthcare in the UK, including the shocking statistic that Black women are four times more likely to die during pregnancy, childbirth and in the first six weeks following childbirth than White women.

Related: The Black Maternity Scandal: Dispatches (Channel 4) and the annual MMBRACE-UK reports on maternal and neonatal deaths.

The Business of Extracting Knowledge from Academic Publications

by Markus Strasser

The author describes his attempt to build tools to help industry extract knowledge from the biomedical literature. He concludes that these kinds of tools are not useful to industry for several reasons, including that the most useful knowledge is in people rather than in papers.

Related: Some good discussion of the article on Hacker News.

Science and Chinese Somatization, or: Do I ‘Feel’ Like a Chinese Person?

by Shayla Love

Researchers have found that Chinese people tend to express psychological distress through their bodies – which is known as somatization. The article describes some of this research, and how it links to cultural differences between China and Western countries.

Why are North and South India so different on Gender

by Alice Evans

Southern and North-Eastern Indian women do better on many measures than women in North and North-West India. The article considers a variety of explanations for this including types of crops grown, conquest, colonialism, and poverty.

People of the Book: Empire and Social Science in the Islamic Commonwealth Period

by Musa al-Gharbi

This paper argues that although social scientists have looked at how their fields have been shaped by Western empires, they haven’t looked much at how social science functioned in other empires. It then describes the work of four Muslim scholars working in the Islamic Commonwealth period to understand how they approached social science and their links to imperial power.

Related: An interview with al-Gharbi on this article and his other work.

Turning an Undergraduate Class Into a Professional Research Community

by Hasok Chang

This paper describes an undergraduate class run by the author on the history of science where undergraduates did original research on a common theme. Each year of the class would build on the research of the previous year’s class, enabling the undergraduates to build on each other’s work and reach a publishable standard.

Related: An Element of Controversy: The Life of Chlorine in Science, Medicine, Technology and War – the academic book published from this work.

Thanks for reading!

We’re always looking for interesting reading materials so get in touch if you have any to share.

We are also currently looking for a health funding design intern.

Develop your skills and gain experience while helping to create a more open, just and responsible philanthropic sector.

The Good Problems Team at Science Practice helps science and innovation funders to identify and act on promising opportunities to tackle pressing global and local challenges.

We’re looking for an intern to join our team for 3 months in early 2022 (remote position). We are looking for curious and passionate people able to bring a combination of lived, academic and/or practical experience in one or more of the following disciplines:

- Health research

- Public health

- User research

- Service design

- Funding programme development

- Innovation research

- Policy research

- Community building

If you are interested in building a better understanding of how funding priorities are set and helping to make this process a more open and participatory one, we want to hear from you.

About us and the role

We are a dedicated team of five with skills ranging from design and research to social entrepreneurship, strategy and community building. Our portfolio includes over 50 innovation programmes designed in collaboration with funders such as the Wellcome Trust, the Humanitarian Innovation Fund, Impact on Urban Health, and Nesta.

We are currently supporting funders to scope and design programmes that:

- Address health inequalities faced by Black and other minoritised communities in London with a focus on mental health, maternal health, and air pollution

- Address priority gaps in pain research through data

- Expand the role of public engagement in health research.

As an intern, you will work as part of our team to support the development and design of these programmes. This will likely include organising and taking part in interviews with stakeholders who have different perspectives and levels of power, developing and testing new programme models, designing and facilitating workshops, and carrying out complementary desk research. You will be mentored by one of our team members who you will report to for the duration of the internship. We will make sure that the projects you are involved in match your interests and skills as closely as possible, and that they offer a relevant learning experience for you.

This role is suitable for someone at the beginning of their career interested in exploring different aspects of working with large funders and developing programmes.

We’re looking for someone who

- Has a combination of lived, learned and/or practical experience in one or more of the disciplines listed above.

- Has robust research skills and enjoys exploring new topics using a range of research methods including desk research and interviewing diverse actors such as scientists, policy-makers, people with lived experience, industry representatives, and civil society.

- Has excellent communication and organisational skills and can effectively support and build relationships with diverse stakeholders.

- Shows initiative and is adaptable and interested in learning from and supporting the team across a range of activities including interviews, workshop design and facilitation, stakeholder management, and desk research.

- Is interested in the philanthropic sector and motivated to improve how funding decisions are made and resources allocated.

- Is generally curious and interested in making connections between ideas, practices, and people from across different fields.

- Can rapidly gain a competent understanding of new topics in unfamiliar domains (in particular, health research) and make judgements based on complex evidence.

- Writes well and communicates complex subject matter in simple, engaging language.

We are advertising this internship as a 3-month opportunity to start in mid–late January 2022, with the possibility to convert to a permanent role beyond this. For this internship, we are looking for applicants able to commit at least 4 days/week over this period.

What we are offering

- London living wage (currently £11.05 per hour)

- Mentorship and the opportunity to develop new skills

- Flexible working arrangements to fit around other commitments, such as coursework

- The ability to work remotely. Our Science Practice team still works remotely to minimise the risk from COVID-19. Our working hours, although flexible, are aligned with the UK timezone; anyone joining the team will be expected to have at least a 4-hour overlap with this timezone.

Right to work

In order to apply for this internship, you should have the right to work in the UK or be eligible to apply to work in the UK through an authorised immigration scheme for work placements.

How to apply

We value diversity at our company. This is core to our work as developing a robust understanding of problems and how to tackle them requires a diversity of thought, experience, and perspectives. We welcome applications from all backgrounds and abilities, and encourage applications from those who identify as members of frequently excluded groups.

Throughout our recruitment process as well as once part of our team, we are happy to consider any reasonable adjustments that employees may need in order to be successful.

To apply, please submit your details via this form.

The deadline for applications is 10am on Monday, 17 January 2022 (extended from 10 January).

We will review applications on a rolling basis.

The application process will consist of two interviews – one with our team lead to discuss the role and your experience, and (if shortlisted) one with the wider team to explore in more detail your interest in the position and relevant experience.

We look forward to hearing from you! 🙌

No agencies, please.

We will soon be working on a project to explore priorities in pain research. To prepare for this, we wanted to get an overview of pain from the point of view of biomedical science, social science, and lived experience.

In this post, we’re sharing the most useful resources we came across and what we learned from them in case they might be useful for others interested in learning about this topic.

Textbooks

Textbooks are great for getting an accessible overview. We looked at a few and found this one most easy to engage with at this early scoping stage: Pain: A Textbook for Health Professionals. There is also Wall & Melzack’s Textbook of Pain which looked too detailed for getting started, and An Introduction to Pain and its Relation to Nervous System Disorders which was too advanced, although may become useful as we get deeper into the project.

Introductory pain science

We used a mix of YouTube videos and a textbook to familiarise ourselves with key concepts and processes.

The Science of Pain (and its Management) covers some of the basics of what pain is, types of pain, and types of drug treatments.

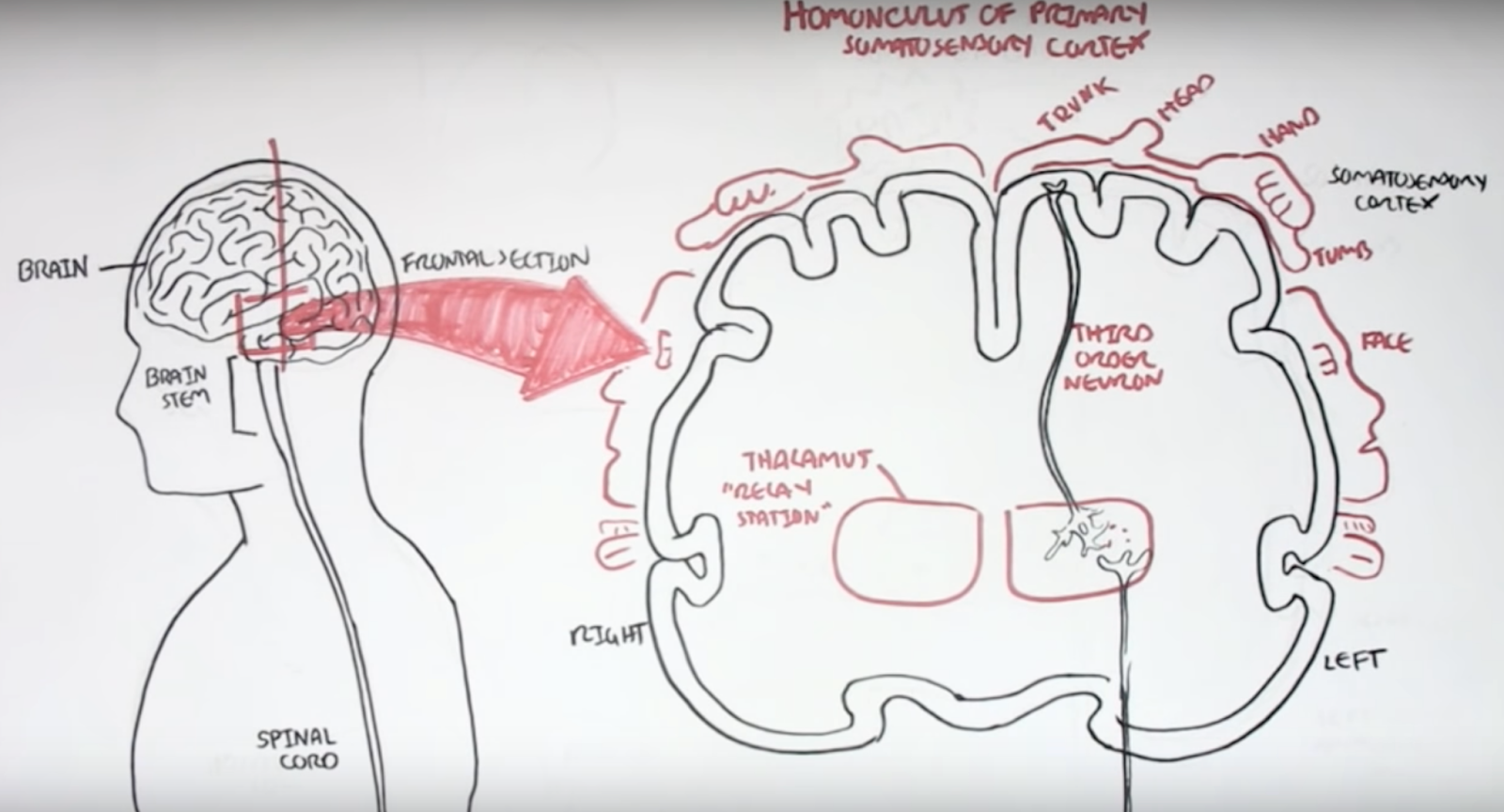

Armando Hasudungan creates videos with hand-drawn diagrams that are easy to learn from. His videos on nociceptors and pain physiology are useful starting points for pain specifically, and he has other videos on neurology such as Neurology - Divisions of the Nervous System.

Dr Matt & Dr Mike have an Introduction to Pain which is dense with clear, introductory information on biological mechanisms of pain and how pain drugs work.

Modern Brain and Pain Science and Implications for Care is an entertaining talk that describes a range of experiments in pain science, particularly on the psychological aspects of pain.

Finally, Section 1 (‘What is pain?’) of Pain: A Textbook for Health Professionals goes deeper on pain psychology, neuroanatomy, and neurophysiology.

Central sensitisation

We got interested in the role of central sensitisation in pain as it may explain how pain can become chronic. Central sensitisation “refers to the amplification of pain by central nervous system mechanisms.”1

We found this video to be an accessible starting point: Dr. Sletten Discussing Central Sensitization Syndrome (CSS). Then Chronic Pain and Sensitisation provides more detail on the biological mechanisms.

The neurobiology of central sensitization gives a detailed overview of the phenomenon. It was particularly interesting to learn about the overlap between different chronic pain conditions, many of which have been grouped under the term Chronic Overlapping Pain Conditions (COPCs), including fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, headache, endometriosis, and low back pain. It may be that all of these conditions have central sensitisation as an important cause. The article says that “many pain experts have suggested that COPCs are best understood as a single lifelong disease that merely tends to manifest in different bodily regions over time”.

The paper also makes a useful division between central sensitisation that is driven by ongoing input from pain sensors, and central sensitisation that has no such ongoing input. Which of these a patient has affects which kinds of treatment are likely to work.

Opioids

We wanted to find out more about opioids given their importance in managing pain and the challenges around the opioid crisis in the US.

A couple of resources helped us get oriented on biological mechanisms. Opioids and Opiates gives a brief introduction to the mechanisms by which opioids work and Opioids describes types of opioids, mechanisms, and adverse effects.

The Opioid Crisis: Past Present and Future is a short talk explaining the causes of the US opioid crisis and potential solutions. It outlines how well-intentioned goals such as listening to patients and taking pain seriously intersected with pharmaceutical company influence and financial incentives to create a problem of overprescription.

However, it’s important to realise that the swing away from opioids since then has caused significant problems in the US. Two articles in Wired describe the challenges that American chronic pain patients have in accessing opioids in the wake of the opioid crisis. In A Drug Addiction Risk Algorithm and Its Grim Toll on Chronic Pain Sufferers, they investigate software used throughout the US to help doctors and pharmacists to evaluate the risk of addiction in patients. How this software calculates its risk scores is opaque, but it has significant influence over prescribing decisions and this can lead to patients being denied medication that is essential for managing their pain.

[T]he most troubling thing, according to researchers, is simply how opaque and unaccountable these quasi-medical tools are. None of the algorithms that are widely used to guide physicians’ clinical decisions—including NarxCare—have been validated as safe and effective by peer-reviewed research.

In The Unseen Victims of the Opioid Crisis Are Starting to Rebel, Wired documents a movement of people with chronic pain campaigning for access to the opioids that they need.

The campaign to keep opioids away from people who abuse them has ended up punishing the people who use them legitimately—even torturing them to the point of suicide. Now they are pushing back, mobilizing as best they can into a burgeoning movement. “Don’t Punish Pain” rallies are taking place in cities nationwide on May 22, and pain patients are organizing a protest at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta on June 21.

Lived experience

We also wanted to learn more about what it is like to live with chronic pain. Chapter 2 of Pain: A Textbook for Health Professionals gave a useful overview. It describes three ways that chronic pain affects people’s lives:

-

The search for restoration – people go through a long and frustrating process of trying to find a diagnosis and cure.

-

Loss – having chronic pain often leads to many difficult losses, such as loss of work, relationships, social roles, and valuable identities.

-

Stigma – people with chronic pain are often treated with suspicion by healthcare professionals and others in society.

The chapter also contains many quotes from people with chronic pain, which are valuable for understanding their experience. This is an excerpt from a quote by Ron:

I’m pretty stuffed I suppose, stuffed in many ways. The consequences of it are, I’ve lost my career, I’m a lousy father in the sense of my ability to handle the kids for more than an hour at a time, there’s no football, running on beaches, the ability to socialise, all those sorts of things I can’t do because movement aggravates pain, any movement aggravates muscle and joint pain. The fatigue denies me any ability to keep my brain alive, so going out to dinner and talking to someone is generally just not on.

We also discovered the healthtalk.org website which collects people’s experience of health conditions through video interviews. They have a section on chronic pain which covers people’s experiences of pain management, medication, and the impact of chronic pain on their lives. This site is particularly valuable as they use rigorous qualitative methods to develop their resources. This means, for example, that they work to represent a wide range of experiences of a condition.2

It was also useful to look at social media to understand more about people’s lives. There are many videos on YouTube where people with chronic pain talk about their experience. For example, this interview with someone with fibromyalgia or this Q&A by someone with trigeminal neuralgia and anesthesia dolorosa.

It’s also useful to read the comments on YouTube videos about chronic pain, as often people with lived experience will share their views. There are often many critical comments on videos of talks by researchers and doctors, which are useful for understanding some of the frustrations that people with lived experience can have with the medical system. Searching Twitter for chronic pain also brings up a lot of discussion.

We hope you found these links useful. If you are interested in learning more about our work in this space, or would like to share other useful resources, then do contact us via email or Twitter.

-

Harte, Steven E., Richard E. Harris, and Daniel J. Clauw. “The neurobiology of central sensitization.” Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research 23.2 (2018): e12137. ↩

-

“To make sure that a wide range of experiences and views are included we use a method called purposive (or maximum variation) sampling (Coyne, 1997). We carry on collecting interviews until we are convinced that we have represented the main experiences and views of people within the UK” – Health Experiences Research Group ↩