Making mental health research stronger by improving collaboration between people with lived experience and researchers

We are building the Lived Experience (LE) Collaboration Platform – an online platform that makes meaningful collaboration between researchers and people with lived experience of mental health challenges easier and more effective.

This project is funded by Wellcome and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

It is co-developed by Science Practice, The McPin Foundation, The MHPSS Collaborative, and a Working Group of people with lived experience, researchers and coordinators, with input from Wellcome and UKRI.

While good resources and examples of lived experience collaboration already exist, they are scattered and often hard to apply. This platform will bring existing trusted materials into one place, show what good collaboration looks like in practice, adapt resources where needed, and co-create new ones where gaps exist.

✋ Interested in taking part in the project?

We’re recruiting around 25 people with experience of collaborating on mental health research projects to join our Working Group and help shape the platform and its content. Read below to find out more about the role and how to apply.

Deadline: 20 October 2025, 16:00 UK time

What we mean by lived experience collaboration

By lived experience we mean knowledge and insight gained from first-hand experience of mental health challenges. People self-identify with this experience – no diagnosis or prior contact with mental health services is required.

In collaboration, people with lived experience join research teams as colleagues and partners. We distinguish between participation – taking part in a study as a research subject, and involvement or collaboration – working with a research team to advise, design, guide, or carry out the work. Involvement helps keep research relevant and ensures findings can be applied in real-world settings.

Carers, parents, and family members also bring important perspectives. While the focus is on lived experience of mental health challenges, carer voices will be included where relevant.

What the platform will do

The platform will be co-developed with a Working Group to ensure it is clear, useful, and easy to use. It will:

- Show real examples of collaboration, including what was tried, what changed and what was learned.

- Provide practical tools such as templates, checklists, meeting guides and role descriptions that are ready to adapt.

- Offer guided pathways based on who you are and where you are in a project.

- Make finding things easy with clear search and filters.

- Use interactive elements where useful, such as quick decision guides or step-by-step prompts.

The aim is simple: arrive with a question, leave with something you can use.

First focus areas

The online platform will also include distinct modules focused on specific aspects of mental health research and collaboration. Together with the Working Group, we will co-develop the first two modules:

- Child and youth mental health collaboration (ages 10–24).

- Safeguarding in lived experience collaboration, particularly when working with people with learning and communication differences (including, but not limited to young people).

Each module will include examples, tools, and guidance specific to its setting.

Who it’s for

- People with lived experience who want to share their expertise to shape research

- Researchers, clinicians and practitioners who want to collaborate well

- Coordinators and managers who support research teams to deliver lived experience collaborations well

- Funders and policy leads who set expectations and standards

Different users will find tailored routes into the same trusted content.

✋ Join the Working Group

We’re inviting around 25 members to help shape the platform and the first two modules.

Please note: all working group members are expected to have direct experience as collaborators on a mental health research project. This means that they have played an active role in defining, framing, advising or carrying out research.

We welcome people with diverse perspectives and collaboration experience, such as:

- People with lived experience of mental health challenges from different backgrounds and regions, including people often excluded from research

- Mental health researchers at all career stages

- Lived experience research coordinators

- Carers, parents, or family members.

🌍 We are especially keen to bring together people of different ages (with a focus on 16–25), career stages, and countries – including those in low- and middle-income countries.

What Working Group members will do

- Share perspectives and expertise on what good research collaboration looks like

- Explore challenges and opportunities in lived experience research collaboration

- Identify the most useful support and resources

- Co-develop platform ideas and module content by reviewing early ideas and sharing feedback

- Work with others in open, collaborative conversations to build a shared vision.

Optional opportunities to contribute include sharing examples or stories of research collaboration, testing early versions of the platform, or joining smaller topic groups.

Time and recognition

- Expected time: ~15 hours between November 2025 and December 2026, mostly through online group conversations and feedback activities

- Payment: £25 per hour, up to £375 for core contributions, with additional payment for optional activities (such as joining smaller topic groups)

- Other recognition: acknowledgements, certificates, mentorship, connections, and other forms agreed with the group.

How to apply

We welcome applications from people with lived experience (including young people aged 16–25), researchers, coordinators, carers, and family members.

Please complete one of the following forms below, depending on the role you’ll contribute from most directly:

👉Expression of Interest (EOI) for People with Lived Experience or Carers who have collaborated as partners, advisors or consultants (not research participants) in mental health research projects: https://forms.office.com/r/jBSy7dDJKA

👉Expression of Interest (EOI) for Researchers or Coordinators with experience of involving, supporting or facilitating collaborations with people with lived experience as partners, advisors or consultants (not research participants) in mental health research: https://forms.office.com/r/PVNDtjQnaN

We recognise that applicants may have overlapping roles and expertise. For example, a researcher may also have lived experience, or a carer may also coordinate involvement. Please choose the form that reflects the perspective you will contribute from most directly.

Deadline: 20 October 2025, 16:00 UK time

If you’d like to apply in another format, for example by voice note or another accessible option, or have questions, please contact Ana Florescu, Project Lead, at ana@science-practice.com.

We’ll support you to apply in the way that works best for you.

What happens after you apply

We aim to respond to all applicants by early November 2025. If we need more information about your application, we may follow up by email.

Applications will be reviewed by the project team to ensure a balance of roles and experiences, with particular attention to including a wide range of lived experiences, research perspectives, and geographies (including low- and middle-income countries).

Joining the Working Group is one of several opportunities to collaborate on this project. If you are not selected this time, please note that there will be other chances to contribute, such as one-off workshops, interviews, or user testing. You can let us know in the Consent section of the Expression of Interest if you are happy for us to keep your details for future opportunities.

When the Advanced Research + Invention Agency (ARIA) asked us to suggest a ‘wild idea’ for one of their opportunity spaces as part of an event invitation, we flipped through our current list of good problems and picked out one of our top areas of interest. Our proposal piqued their interested and they invited us on stage to pitch it. ICYMI, we’re sharing it here. Note that this is an idea we’re still developing, so it’s ripe for feedback and we’d love to have a conversation about it if it interests you, too – get in touch!

Our pitch

At Science Practice, we have worked extensively with research and innovation funders, and many of our projects have been in health. Informed by our practical experiences carrying out research and design work, and by the lived experience expertise within our team, one of the areas in which we’ve developed a deeper interest is how to accelerate progress in mental health science.

Our ‘wild idea’ for an opportunity space is Modular Mental Health.

We know that globally, mental health conditions represent an enormous and rising burden of disease.

We also know that recovery from mental ill health is possible and there are cases where people have achieved this; however, it can be very difficult to do. People who have managed to find what works for them have generally had to put enormous time and effort toward this, and have often had to go it on their own.

Is the problem that we need more innovation in treatments because we don’t yet have the right ones? It’s worth considering that this is only part of the puzzle.

Perhaps what really needs attention is the way we put treatments together: better menus of treatment options, clearer pathways to systematically navigate these, and infrastructure that supports the kind of personalized experimentation that’s needed for recovery in a much more comprehensive way.

To enable this, we need research and practice that helps us propose and test different ways to match people to appropriate treatments, and to identify which sequences and combinations of treatments people should pursue. We also need to do this in a way that gives people genuine agency over their own mental health journeys – and that doesn’t solely depend on health systems already stretching to meet demand.

Learn more about our new specialism in mental health and wellbeing.

How can we help researchers, funders and young people collaborate more meaningfully in mental health research? Over the past six months, we worked with Wellcome and UKRI to try and answer this question.

Meaningful collaboration with people with lived experience makes research better. It improves research outcomes, aligns research priorities with actual public needs, and creates a more inclusive and rewarding research culture. When it comes to mental health research, collaborating with young people is especially important given how significant early intervention is in improving mental health outcomes. We need young people’s input on what is researched, and how, so that we can advance knowledge and practice that reflects real experiences and responds to urgent needs. However, those interested in collaboration often encounter obstacles that make this work tricky, and when they go looking for solutions, they may struggle to find resources that can help them.

In this post, we share key challenges and barriers facing collaborators in mental health research, particularly young people, researchers, engagement specialists, and funders. We also review some of the existing resources currently available to overcome these challenges. Finally, we reflect on the types of resources out there and theorise how they respond to three distinct learning needs that collaborators have – needs which could be better supported through developing, assembling, and referring to appropriate types of resources.

In this post, we use the term collaboration to refer to working with and alongside people with lived experience in research. This is distinct from participation in research, where members of the public share data rather than expertise. Collaboration is a broad term covering many different ways researchers work with people who have lived experience, including, but not limited to, patient and public involvement (PPI), participatory research, and community engagement.

Challenges & barriers

Any good resource in this space needs to tackle the factors that make research collaboration difficult. To identify and understand these, we spoke with over 30 stakeholders with different perspectives and experiences of collaboration. This included researchers with years of engagement expertise, youth mental health charity staff, early career researchers on international youth mental health collaborations, experienced engagement coordinators, funders of youth mental health organisations, and young people aged 15–29 years. We spoke with people from the UK and globally, including collaborators based in Australia, India, Kenya, South Africa, Uganda, the US, and Zimbabwe. Those we interviewed highlighted the following challenges and barriers preventing meaningful collaboration:

-

Recruitment & retention: Successfully reaching and recruiting a diverse range of young people to collaborate with can be difficult. Usually, collaborators are sourced through word of mouth or existing networks, making it harder for researchers to reach under-represented groups.

-

Legal & ethical barriers: Legal teams often don’t know how to treat young people under 18 as experts by experience rather than participants. Are they employed, or reimbursed? Plus, there is a need for parental consent, and this takes time and requires trust between researchers and families. Additionally, there is a lot of siloed working and lack of coordination between health trusts and universities when it comes to collaboration, so many are addressing the same administrative problems in slightly different ways.

-

Youth capacity: Arranging collaboration activities around a young person’s availability can be difficult, considering they can be at school or have exam schedules. Zoom meetings and other research environments may also be unfamiliar to young people, and they need time to adjust and gain the skills to contribute in these settings. Researchers need ways to meet young people where they are, rather than expect them to immediately adjust to academic ways of working, and young people need adequate support structures so that they can contribute to research to the best of their ability.

-

Lack of trusting relationships: Short project timelines mean that researchers don’t have much time to develop relationships with the young people they work with, and this limits the potential for meaningful collaborative work to take place. However, this is challenging when working with young people, as they age out fast. In addition, there can be a level of mistrust of researchers, especially amongst certain communities, and this prevents people from wanting to collaborate.

-

Jargon: Researchers need ways of translating complex scientific medical jargon into language that young people can understand and engage with. In addition, sometimes researchers can use medical terminology that young people don’t necessarily agree with and may feel strongly about, particularly in the domain of mental health.

-

Power dynamics: Power dynamics can be a barrier, both subtly and explicitly. For instance, when young people are at a meeting with researchers or funders, they may feel intimidated and this can affect how they contribute. There are also more practical challenges to work through: How much weight should be given to a young person’s views on a funding panel? What happens when young people disagree with researchers, and how should disagreements be settled when there are differing levels of expertise between them? Collaborators need to be trained in how to navigate these issues.

-

Inclusion & customisation: People from different groups have different needs, whether this is because they come from differing cultural backgrounds, have accessibility requirements for their mental health condition, or are within younger or older age ranges. Making adequate customisations is essential, but there is little guidance around how to do this.

-

Not valuing lived experience: Young people sense when researchers don’t ‘get it’, when it comes to valuing lived experience expertise. A tokenistic approach disadvantages both researcher and young person when trying to work together, because the collaboration remains surface-level and not meaningful.

-

Youth interest: Young people can have certain preferences or expectations for research they would like to be a part of, and researchers often find they struggle to match these expectations. Young people often want to do work that leads to immediate outcomes, however research isn’t always like this.

These challenges and barriers demonstrate how complex collaboration can become. With so many moving parts and differing needs to accommodate, many different resources are needed.

Existing resources & their limitations

Defining a resource as anything which collaborators could turn to for help and guidance, through further research we discovered over 180 resources created to address such challenges and barriers to collaboration.

The resources we found cover a wide variety of formats and perspectives, originating from disparate sources representing distinct theories of collaboration in very different disciplinary, institutional, and population contexts. They include materials and tools in the form of blog posts, templates, and webinars, but also more relational resources such as networks of young people. They were developed by charities, consultancies, universities, funders, as well as individual researchers and young people. Some focus on collaboration within mental health research whereas others are geared toward research collaboration more broadly. Some address specific collaboration considerations at particular stages of the research process. Some are designed for public and patient involvement (PPI); others for community engagement. Some provide basic, foundational guidance, and some assume users are already somewhat experienced in collaboration so don’t refer to more basic principles or frameworks.

We also noticed clear gaps in the available resources. Most are aimed at researchers, while fewer are targeted at funders and young people. There is a conspicuous lack of materials developed specifically for research collaborators in low-resource settings or in specific social or cultural contexts globally. Furthermore, guidance tends to focus on certain challenges and barriers more than others. For example, we found that more general resources on power dynamics and valuing lived experience are relatively plentiful, whereas those on the practicalities of recruitment and retention, inclusion and customisation, and legal and ethical barriers are much rarer.

Overall, our analysis revealed that while many mental health research collaboration resources already exist, what’s currently available is heterogeneous and scattered widely. This can make it difficult for collaborators to locate and piece together what they need, when they need it so that they can ultimately formulate a meaningful collaboration approach backed by good practice.

Meeting learning needs of research collaborators

One way to help research collaborators navigate the myriad resources on offer is to lead with their learning needs. Many people we spoke with shared strong testimonials for particular types of resources, whether theoretical frameworks, training and guidance, or stories of experience. We found that these endorsements generally reflected one of three distinct learning needs: the need to establish the right mindset, to refine methodologies, and to improve practice. Below, we describe each of these learning needs in more detail and give examples of resources which address them.

1. Establishing mindsets by understanding collaboration theory

When people need to understand what good collaboration is and why it is done, they find it beneficial to look at theoretical frameworks, sets of principles and values, and opinion papers. These tools support a mindset shift toward understanding, valuing, and integrating meaningful involvement of people with lived experience in research. Theoretical frameworks can also provide a heuristic against which collaborators can check their proposed approach, and allow collaborators to position their approach in relation to other styles of working. For instance:

-

A funder wanting to recruit youth advisors might use a theoretical framework such as Roger Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation to understand the level at which collaboration may be useful to them and why.

-

Collaborators can read sets of principles and values, like those listed within the WHO’s meaningful engagement framework of people living with noncommunicable diseases and mental health conditions, to understand the foundations of how to work together.

-

Researchers can also read opinion papers, like this one on how to re-conceptualise authentic patient engagement roles in youth mental health research, to understand the relevant concepts and nuances which become present in this work.

2. Refining methodology through training and guidance

When people need to design and carry out collaborative work, they find it useful to have clearly outlined instructions for how to attempt the many varied aspects of collaborative work. This includes planning research activities, fulfilling ethical and legal requirements, and making the appropriate changes to processes and activities when working with particular groups. Having detailed guidance means that collaborators can learn from best practice and incorporate these learnings into their methodology. For instance:

-

A young peer researcher may use a training course like King’s College London’s guide to community and peer research to learn how to effectively and ethically conduct research.

-

A researcher may use worksheets and templates such as those featured on Imperial’s Public Involvement Resource Hub to help simplify processes across the entirety of a collaborative research project.

-

Collaborators can benefit from toolkits and guides, like the Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre’s Enabling Participation guide, which offers procedures, recommendations and practical dos and don’ts for those wanting to collaborate with young people in research.

3. Improving practice through experiences

When people need advice on how to improve their collaborations, they often look to experiential knowledge sources to help inform their practice. By reading about others’ experiences in case studies or reflective articles, or speaking directly with peers in networks, collaborators can learn what works more and less well across collaboration contexts. They can use this information to craft solutions for project-specific problems and accumulate learnings to shape their holistic perspective over time. For instance:

-

A researcher may look to a case study, like this one, which describes learnings from co-producing a randomised-controlled trial, to understand the successes of a project and any other important considerations which they could take into their own work.

-

A young person may read another young person’s reflective blog post, like this one by Boing Boing youth advisors, to understand what to expect from working alongside researchers at an overseas research conference.

-

A funder may look at project evaluations like the Islington Giving Young Grantmakers evaluation to understand how a project went, the approach used, and the resulting impacts.

Finding the right resource at the right moment has the potential to critically impact the success of a mental health research collaboration. However, with such a wide variety of resources scattered across many locations, this doesn’t always happen. In addition to strengthening the resource offering, there is a need to make this space more navigable so that research collaborators can find resources that really help them.

Whether we are developing more resources, strengthening existing ones, or collecting them together in databases, toolkits, or other platforms, we should prioritise addressing the known challenges and barriers to collaboration. However, we should also consider collaborators’ distinct learning needs. Knowing whether a group of mental health research collaborators have greater interest in learning how to establish the right collaboration mindset, refine a collaboration methodology, or improve their collaborative practice can indicate which types of guidance will be most relevant for them – and which resources we should develop, gather, and share in order to better support meaningful collaboration.

For the past year, we’ve been cultivating an interest in mental health and wellbeing, particularly the role that spirituality and meaning can play in this. From this interest we’ve been developing a programme of work that we’re introducing with this post.

Science Practice works across many different domains and cause areas, but we have recently created a stream of work focused on mental health and wellbeing. We use ‘wellbeing’ as well as ‘mental health’ for a couple of reasons. Firstly, this term includes a wider range of problems – we’re interested in improving people’s wellbeing even if they don’t have a diagnosable mental health condition. Secondly, it includes a wider range of thought and practice – bringing in ideas, frameworks, and solutions from outside of the health field.

This interest has developed out of our personal experience, long-time intellectual curiosity in this area, and a steadily growing portfolio of work we’ve done for funders.

Through our own experiences, we’ve gained a deep understanding of how mental health issues can alter and challenge daily life, and we’ve experimented with a mix of methods and techniques to deal with these difficulties to varied effects. We’ve also seen friends, family, and members of our communities suffer from mental health issues and have become more generally concerned about widespread mental ill health among young people.

This concern is heightened by social forces which can impact mental health, such as social media, social isolation, and sedentary lifestyles, plus the inadequacy of current mental health care systems to meet demand and sufficiently tackle the problem.

We’ve been excited by newly emerging possibilities for tackling this problem, some of which are genuinely new and some of which are rooted in ancient traditions. The most hyped is psychedelic psychotherapy, but others that also look promising include body-focussed trauma therapies, a wide variety of meditation and spiritual techniques beyond mindfulness, group approaches such as men’s work and women’s work, and simple therapeutic techniques that can be done alone or with peers. For this reason, a major area of interest for us is practices and techniques outside of current clinical mental health, with a particular interest in spirituality broadly considered.

We’ve also been inspired by reading accounts from people who have significantly improved their wellbeing. They have often followed a complex path that involves psychotherapy, meditation, psychedelics, self-therapy techniques, and more. While these are only anecdotal, they do suggest change is possible when people can find the right combination of solutions for them, and use these in the right order.

Similar directions have emerged out of our client work in the areas of wellbeing and lived experience. For instance, the idea of highly-customised, self-created solutions also came up in a project where we explored research priorities for chronic pain for the Wellcome Trust. When talking to people with lived experience, it was apparent that they had developed complex, customised methods to cope with their conditions. We’ve noticed a great deal of untapped expertise on customised interventions among people with lived experience, particularly people with lived experience of recovery.

As our interest in mental health and wellbeing has grown, we’ve become increasingly motivated to contribute to solving the problems we see. As researchers and designers with existing expertise in problem identification, grantmaking ecosystems, and funding programme design, we’ve been looking at our existing knowledge and skills to figure out what role we can play in advancing progress in this exciting area. We’re also aware that this is a very messy space, where it is difficult to understand what is credible, what works, and what is safe. Thinking about evidence and epistemology will therefore be crucial.

Directions we’d like to pursue

We think this is a timely and important moment to further define, grow, and evidence the field of mental health and wellbeing. Drawing on our expertise in doing strategic work for research and innovation funders, here are several areas where we think we would be best placed to contribute.

Landscaping work

We’d like to help funders and other field-shapers to understand what is already being done, what the gaps are, and what promising directions they could support.

-

Funder strategies: Landscape mapping to understand the range of possible strategies that funders could take in this space. This would involve understanding key strategic debates in mental health research funding, the positions different funders take on these, and gaps that funders could fill.

-

Spirituality landscape: A landscaping project to map out the space of spirituality and wellbeing, with the aim of understanding what research work has been done, how it intersects with mental health, and where the gaps are. We’d also like to understand how research funders could support work in this space.

-

Understanding breakthroughs: Research to better understand where valuable breakthroughs and interventions in mental health have historically come from and the conditions that enabled them, particularly looking at interventions that come from outside of academic mental health science.

-

Informal mental health practices landscape: Many people turn to practices outside of clinical mental health services. Research to better understand what informal practices people turn to and why, and what kinds of effects they have could help identify potentially impactful practices.

Building funding programmes for specific types of research

We would like to work together with funders to design and run funding programmes that target important gaps in the landscape such as:

-

Recovery case studies: Fund qualitative work gathering case studies from people who have recovered from mental health conditions to understand the full complexity of their recovery pathways. This could then be used to inform funding and research agendas that attempt to understand and work with this complexity.

-

Impact evaluation of wellbeing practices: Fund impact evaluation of interventions that practitioners and people with lived experience think are helpful, but for which little scientific evidence exists.

-

Methodological issues in mental health and wellbeing: Fund work to address methodological issues that crop up in studying spiritual and other non-medical wellbeing practices for mental health and wellbeing, such as blinding, consent, and the adequacy of self-report.

Convening and field-building

As we build up connections in this field, we’d like to bring together people who share an interest in the intersection of mental health and wellbeing, and spirituality.

-

Bringing research expertise together with practitioner knowledge: There is potentially a wealth of practitioner knowledge with unrealised potential. To better establish, consolidate, scale, and document this, we need to build connections between practitioners and researchers.

-

Supporting dialogue and debate in sub-fields with distinct, competing approaches: For example, in psychedelics, some favour a more medical-based model, whereas others advocate for community-led approaches. Creating a space where these perspectives can interact and build on each other could help advance the conversation.

-

Bringing people with lived experience together to share their own mental health and wellbeing pathways, challenges and successes: This could contribute to building up an understanding of what kinds of things help people improve their wellbeing and recover from mental health issues. Stories from this could be used to develop the recovery case studies mentioned above.

There is a huge need for greater wellbeing, and many promising solutions, but this is also an area with a history of hype, disappointment, and harm. We’d like to work together with funders and other field-shapers to further define and develop this space and contribute to better mental health and wellbeing for everyone.

If you are interested in pursuing these directions and ideas — as a funder, researcher, practitioner, or person with lived experience — get in touch with us at rb@science-practice.com. We’d love to hear from you.

Funding practices do not always lead to the equitable outcomes we hope for. To help address this, we supported Wellcome’s Culture, Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (CEDI) team to identify innovative practices that other organisations have used to address inequities in funding outcomes. This post introduces the Equitable Funding Practice Library we developed and shares how funders can use and build on this resource.

Through this project, we set out to put grant makers at Wellcome one step ahead on their journey toward achieving more equitable funding outcomes by identifying existing practices that they could build on, adapt, and refer to when designing their own context-specific interventions.

To do this, we explored the practices of many different funders working with many different sectors, populations, communities, geographies, and scales of implementation. We also looked beyond funding into other domains to see what was being done to improve equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) outcomes within recruitment, university admissions and prize mechanisms.

We found more than 100 distinct methods, models, approaches, and ways of working funders have used to address funding inequities. Ultimately, we built a collection featuring 50 of these practices in greater detail. We’re excited to share this resource today.

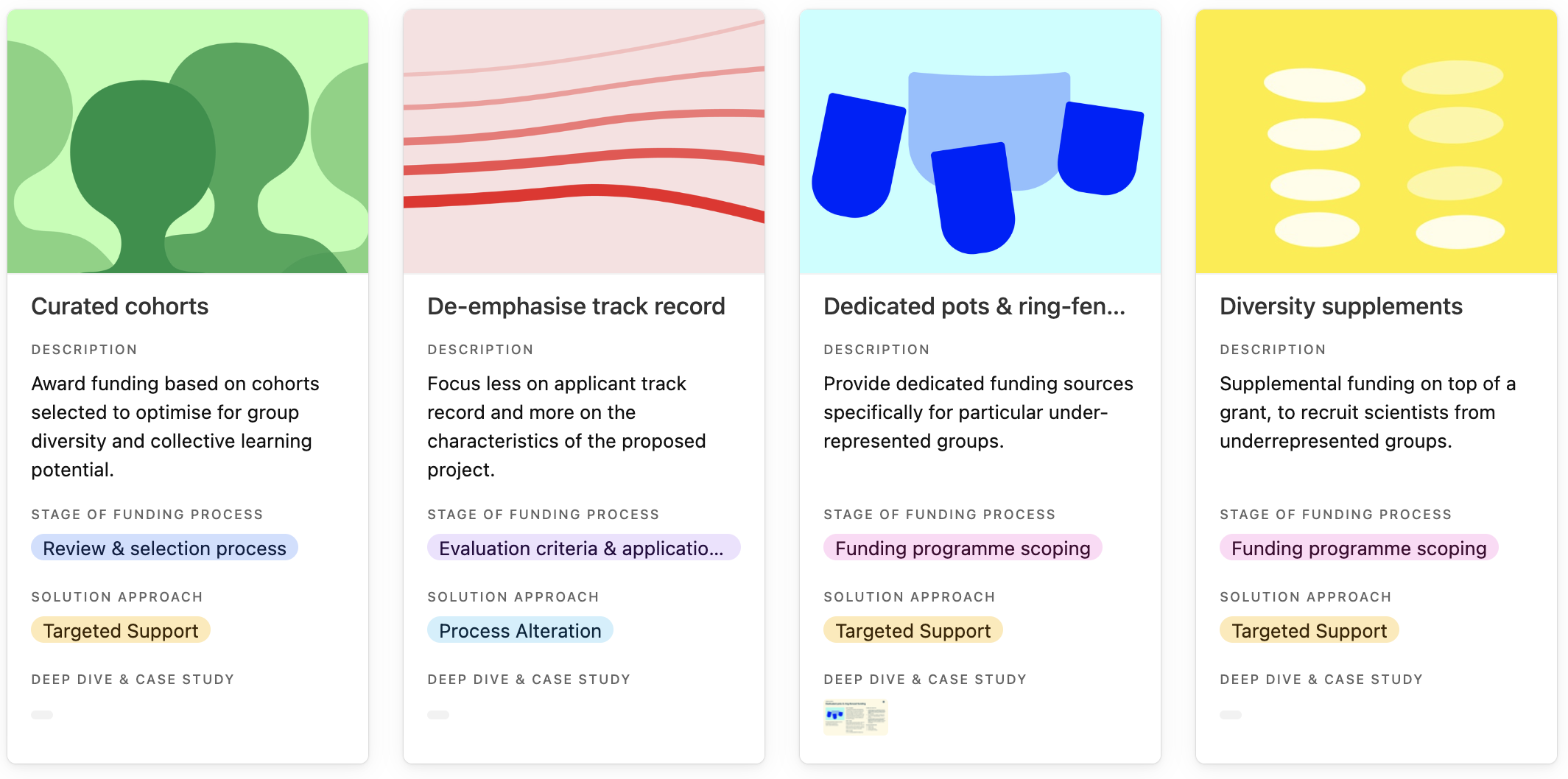

What’s in the practice library?

The Equitable Funding Practice Library brings together repeatable ideas that can be mixed and matched or applied individually to solve common challenges in reducing and eliminating inequitable funding outcomes. Whether you’re a funder, grantee, applicant, advocate, or anyone else working to make funding outcomes more equitable, we hope you’ll find this collection of practices a useful reference and source of inspiration.

Explore the Equitable Funding Practice Library

For each featured practice, the library provides a short description of what the practice does. Users can click through for further details including why the practice is needed and examples of the practice in implementation. For a subset of 10 practices, we’ve also attached a more detailed profile and case study, highlighting implementation tips and insights as well as evidence of success where available.

Entries in the practice library, curated cohorts, de-emphasise track record, dedicated pots & ring-fenced funding and diversity supplements.

How to use this resource

1. Browse the practices for inspiration

Browse the practice library to get ideas for how to address EDI challenges that persist in funding systems, programmes, and processes. Click on each practice to read the ‘why its needed’ field to understand the types of challenges a practice has addressed, and whether it could help you address similar challenges.

You can search, filter, and sort the practice library.

2. Identify practices at relevant stages of the funding process

Determine where in the funding process your own EDI challenges arise, then view the practice library by stage of the funding process to identify which practices could be relevant to your situation. Keep in mind that some practices may have relevance across multiple stages, even if the practice library only lists one stage.

The funding process, from establishing the funding opportunity, through designing the decision-making process, to implementing the application process.

3. Discover practices by solution approach

You can also explore practices that match the solution approach most relevant to the scale of change you are aiming to achieve, and whether you would prefer a targeted or neutral strategy. Use the following questions to understand which solution approach best matches your interests. Then, view the library’s practices in that category.

- Are you interested in giving certain groups of applicants dedicated sources of support to help them through a process? Explore practices in targeted support.

- Are you passionate about changing the traditional funder-grantee power dynamic and shifting the power into the hands of communities who are most marginalised? Explore practices in shifting power.

- Are you interested in identifying the causes of disparities and addressing these proactively to make sure all applicants have an equal chance of succeeding? Explore practices in process alteration.

- Do you want to avoid complex EDI interventions and wipe the slate clean, introducing new models of funding which even the playing field from the start? Explore practices in radical simplification.

In the solution approach matrix, the four solution approaches are: targeted support, shifting power, process alteration, and radical simplification.

4. Build your own interventions

The practices we’ve gathered are starting points to build on. We invite you to adapt what you discover in the library to ultimately create your own interventions fit for your particular context. If practices in this resource have helped you reduce inequities in funding outcomes, please get in touch to share your experience with us.

To suggest practices to add to the Equitable Funding Practice Library, share your experience using this resource, or learn more about this project, contact Gearóid Maguire or the Science Practice team.