Over the past 12 months we’ve been working closely with Nesta’s Centre for Challenge Prizes to design a set of 10 prizes for the European Commission. Our scope was broad – identify technical challenges or problems that require technological solutions.

It’s been an intense year with over 100 expert interviews, several dozen topics reviewed and a lot of lessons learned along the way. While the topics of the prizes are still under wraps, we thought we’d share some of the key things we learned from this process of finding good problems and transforming them into ambitious prizes. Here goes:

-

New, potentially disruptive technologies are often clouded by technical language which may limit their wider adoption. A prize can be helpful to clearly articulate the technology, offer legitimacy and introduce it to different communities.

-

Designing a prize that would operate in a billion-dollar industry is tough because million-dollar incentives can easily get lost in billion-dollar oceans. But financial incentives are not the only benefits of a prize. A prize can also raise awareness of the shortcomings of well-established technologies and potentially motivate innovators to fix them.

-

At a completely different scale, we designed prizes for technologies that are currently at a very low level of maturity but could potentially revolutionise entire fields. A prize can be helpful as a way of defining a common list of success criteria that people could work towards, as well as raising awareness. This would allow for a fair comparison of solutions and support future development.

-

Prizes can also shed light on who is working on a problem and how much real progress they have made. For one of the prize topics the experts we consulted said that, for decades, innovators who claimed to have solved a particular problem had also failed to translate their discoveries into reliable, marketable solutions. What they did manage to do, however, was to create the impression that the problem was solved and therefore dissuaded others from attempting their own solutions. A prize in this area would have the opportunity to open up the challenge to a wider audience of problem-solvers, set a clear deadline, and require those working on solutions to be upfront about the status of their innovations.

Drawing a line under these findings, what stands out is the need to ensure that the problems we are trying to solve are good ones. By ‘good’ we mean genuine problems that are clearly defined, problems that address a real need, and that stand a reasonable chance of being solved with the resources at hand. We’ve written about this before, but finding ourselves face-to-face with this conclusion once again points to the fact that defining a good problem requires asking the right questions and no small amount of effort. We will be spending this year looking at ways to formalise this process of finding good problems. Stay tuned!

In February 2014 we started work on the Longitude Prize. How we approached this project and what we learned along the way is the topic of the following posts:

After almost four months of interviews with over 100 experts and multiple design iterations we had accumulated a lot of valuable knowledge; the next step was to synthesise and validate this knowledge with a wider expert audience. We began writing up the six challenge prize design proposals into ‘challenge reports’.

Writing these initial reports wasn’t an easy task. We wanted them to offer readers a guided explanation of the decisions made during the research and design process. We wanted to show where there was a clear consensus, but also highlight areas that were still in need of further discussion.

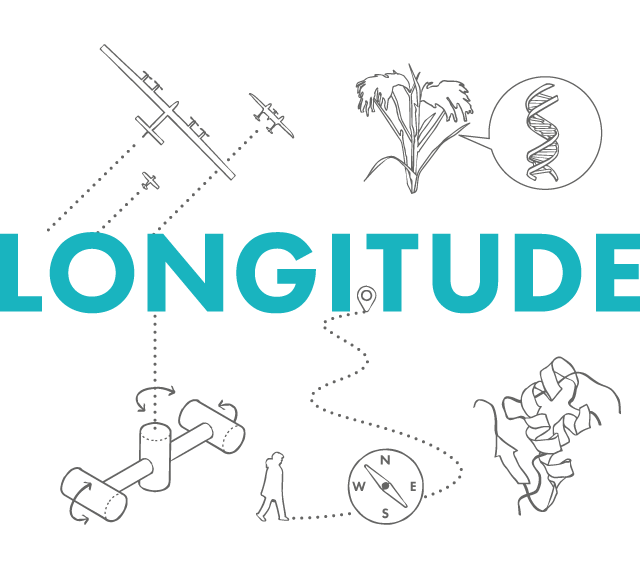

To do this we structured the reports to reflect our research process. Reports began by describing the broad problem area, then gradually started focusing in on the challenge area, the role the challenge prize would play in addressing the core problem, and the types of solutions encouraged. This gradual ‘zooming in’ allowed us to present our arguments and the decision-making process behind the proposed design. It also meant that a contentious element or argument could be traced back to an initial decision point that could then be discussed.

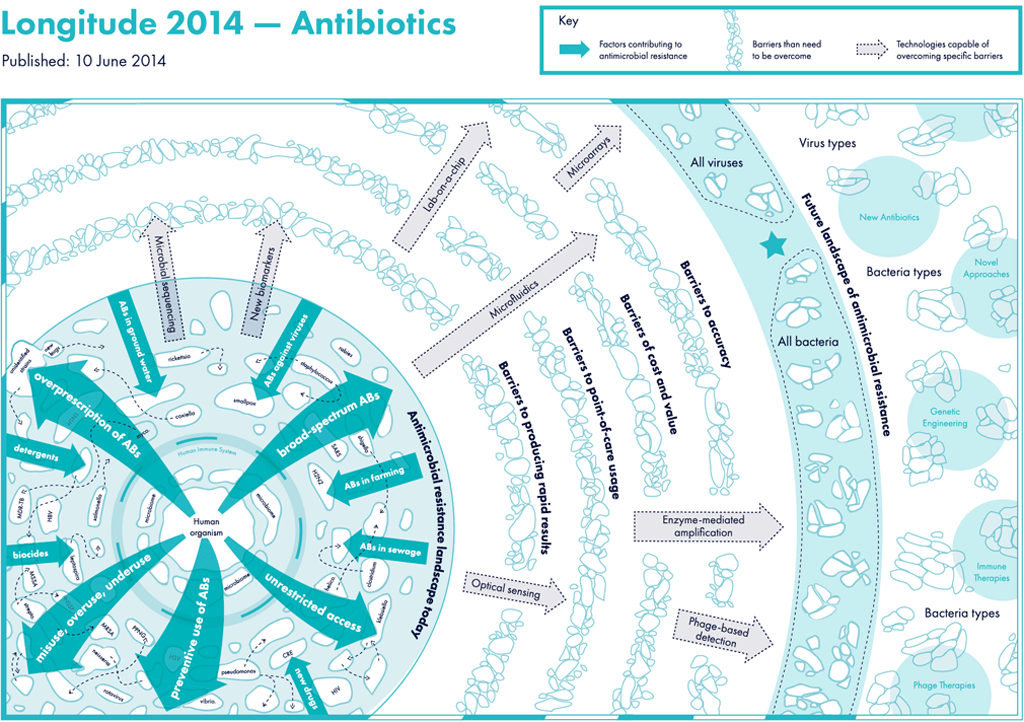

Diagram showing the decision points for the Antibiotics prize with our recommended option at each stage

Challenge Reports in Practice

Once written, we validated these reports with experts. This time around, we wanted experts to act as reviewers. We wanted them to understand that the document we were presenting to them was close to a final challenge prize design, but we still wanted them to actively contribute to its structure. For this purpose, we scattered questions throughout the reports and added an Appendix with key issues other experts brought up in previous conversations.

Although we are aware that there is nothing particularly original about this process, it was very valuable for us as it drew attention to misunderstandings and oversights on our part.

After several iterations each challenge area had an accompanying report that narrated the journey of designing its challenge prize and the decisions made along the way. All we needed to know now was which one of these challenges was going to become the Longitude Prize 2014.

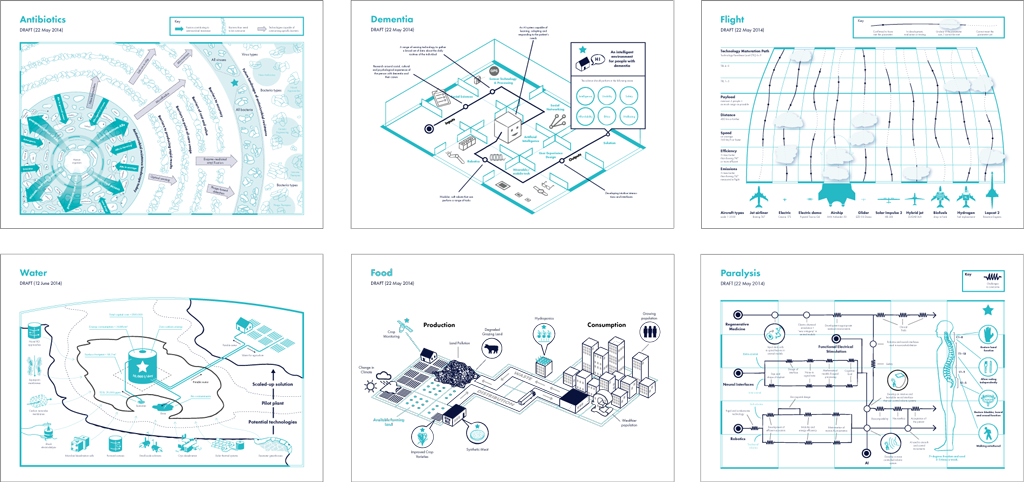

All six Longitude challenge reports

And the Winner is…

Dr Alice Roberts announcing the result

On 25 June 2014 Antibiotics was announced as the winner of the British public’s vote to become the topic of the Longitude Prize. Following this announcement, a decision was made to share the Antibiotics challenge report with the general public to get a broader input on the proposed prize structure.

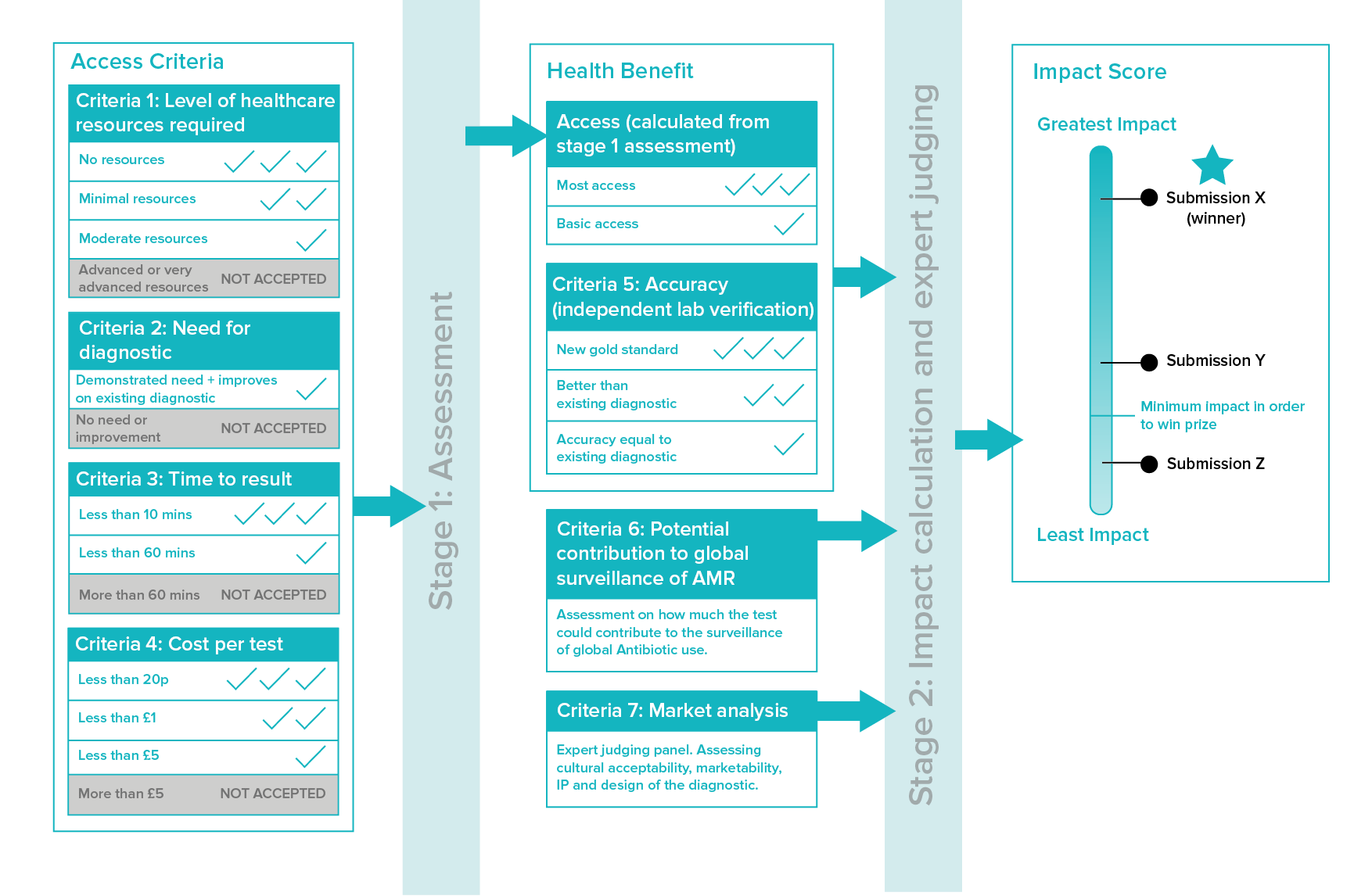

To make the report more accessible we included some additional features. We added illustrations for some example diagnostic tools to make the types of solutions sought more concrete. We included additional visualisations to support the parameters and, most importantly, we added a diagram of the prize assessment process to help competitors understand what is expected from them at the different prize phases.

Diagram explaining the Longitude Prize assessment process

Following these changes, the Antibiotics challenge report was published on the Nesta website with the aim to engage the general public in discussions around the Longitude Prize and get their feedback on the structure of the Antibiotics challenge. Based on this report and the feedback from the open review the final Longitude Prize 2014 Prize Rules were created.

Wrapping up the Longitude Project

The experience of researching and designing the six candidate challenges for the Longitude Prize was a very valuable one for us. It gave us the opportunity to explore new ways of engaging with experts and learn how to make best use of their expertise.

In our write up of this project we have placed an emphasis on the design proposals we used to prompt discussions. We did this to highlight their role in supporting more focused, specific and constructive discussions. At a more fundamental level, this process meant that the researcher took responsibility for the creative quality of the ideas being discussed - something that can often lack in research that seeks to canvas the opinion of many stakeholders.

Now that our work on the project is done, we’re eagerly looking forward to seeing the innovations the Longitude Prize 2014 will bring!

You can read the full Antibiotics challenge report here and the Prize Rules here.

Think you’ve got an idea about how to solve the Longitude Prize 2014? Register your team here. Good luck!

In February 2014 we started work on the Longitude Prize. How we approached this project and what we learned along the way is the topic of the following posts:

In our previous Longitude Prize post we introduced challenge mapping which was our process for gaining enough understanding of the six challenge areas to start designing the challenges themselves. This post is about prototyping and testing different formulations for each challenge.

Similar to the previous research phase, we could only do this by talking to experts. This time around, we wanted them to think like competitors. We needed to understand whether the challenges we were proposing were right. Would they inspire healthy competition and novel solutions from a wide field of participants? Were they good problems?

Before we started the next round of interviews we wanted to create a proposal to stimulate discussion. So we came up with something called a challenge prototype.

The structure of a Challenge Prototype

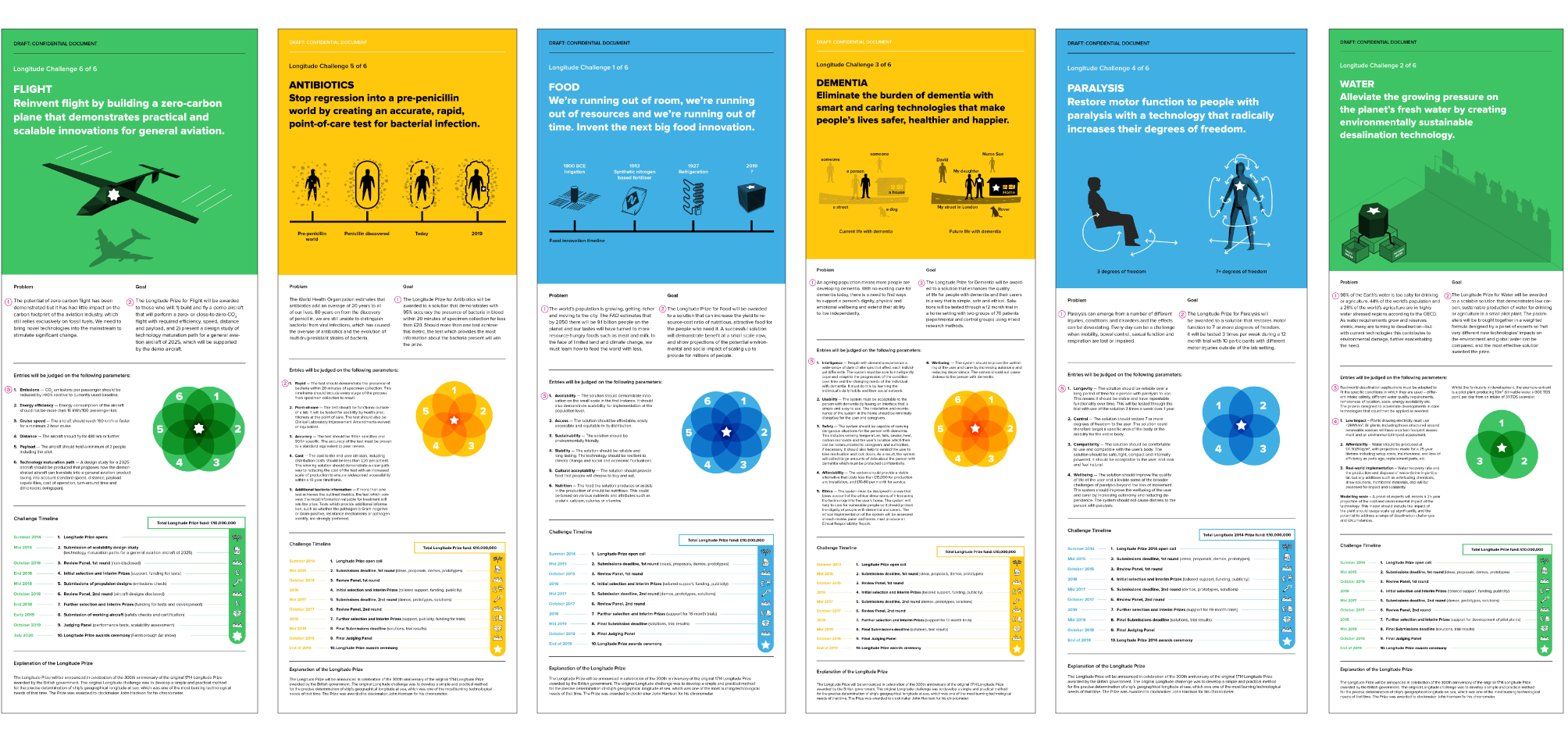

Despite the fancy name, challenge prototypes are pretty simple, one-page documents which summarise a challenge. They state the vision of the challenge, define the problem to be solved, set the goal to be attained, detail the judging criteria and, lastly, spell out the logistics of taking part: deadlines and prize money.

All six Longitude challenge prototypes

By talking through these prototypes with experts we wanted to validate the conclusions we drew following the challenge mapping phase as well as get a better understanding of how competitors would approach such a prize. We wanted to move from the hypothetical to the concrete and get into the details.

Understanding competitors

Each interview started with the problem and goal statements in the prototype. When an expert disagreed with the proposed challenge, discussing these two statements helped us understand whether this was due to our framing of the problem, or the solutions we were expecting.

The most detailed conversations generally took place around the judging parameters and timelines. We wanted to know whether the judging criteria made sense and whether they were objective enough for solutions to be assessed against them. Equally important, we wanted to know if the challenge had a reasonable chance of being solved in the given timeframe and understand what kind of support could motivate and encourage innovators along the prize journey.

Stating the judging criteria with specific targets and limits - even if these weren’t necessarily the right ones – helped engage experts in detailed conversations around what form potential solutions might take and how they could be assessed. This allowed us to get a feel for the dynamics between the individual criteria and how they fit together.

One of the unexpected benefits of having the challenge written down were the corrections we received to our (often clumsy) use of specialist terminology. These are the types of mistakes that don’t get picked up in conversation, but stood out to experts on paper.

The last question we asked the experts we interviewed was whether they would take part in the challenge as described. If the answer was ‘yes’, then this was a positive sign that we were getting close. If the answer was ‘no’, then this was a good opportunity to ask why.

In February 2014 we started work on the Longitude Prize. How we approached this project and what we learned along the way is the topic of the following posts:

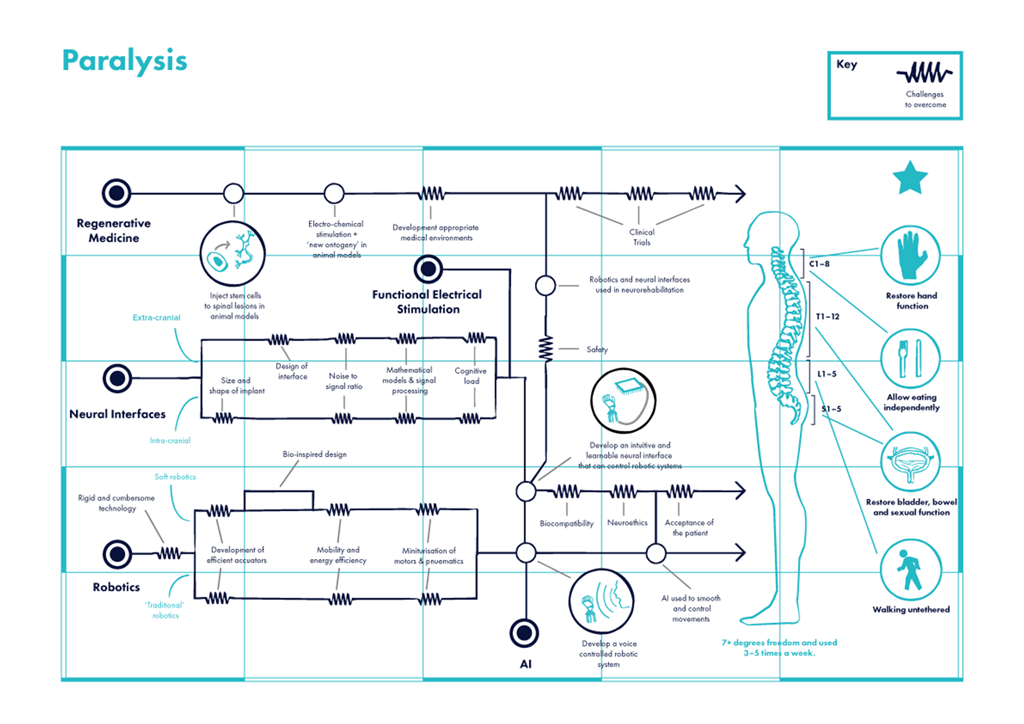

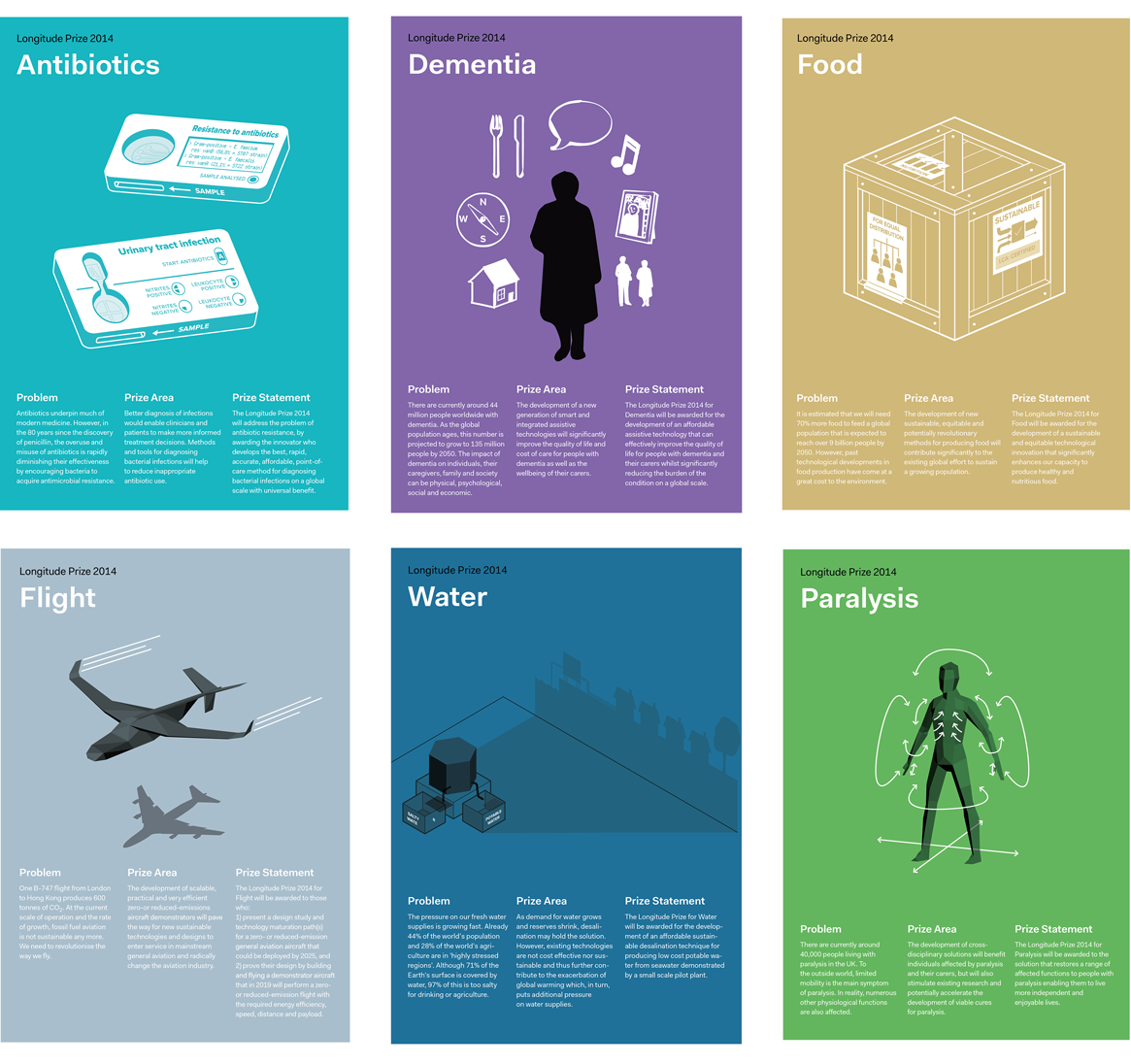

Antibiotics, Dementia, Flight, Food, Paralysis, and Water. Our first task on the Longitude project was to map out the main barriers to innovation within each of these areas and understand what are some of the most promising routes towards a solution. Given the short timeframes of the project, how could we best engage with the expert community to build this understanding?

At Science Practice, we take a design-led approach to research. Plainly put, rather than asking experts to tell us their opinion on a topic, we present them with a specific proposal and seek their response to it. We often refer to this proposal as ‘research stimulus’. For this first phase of the Longitude project the research stimulus took the form of a map.

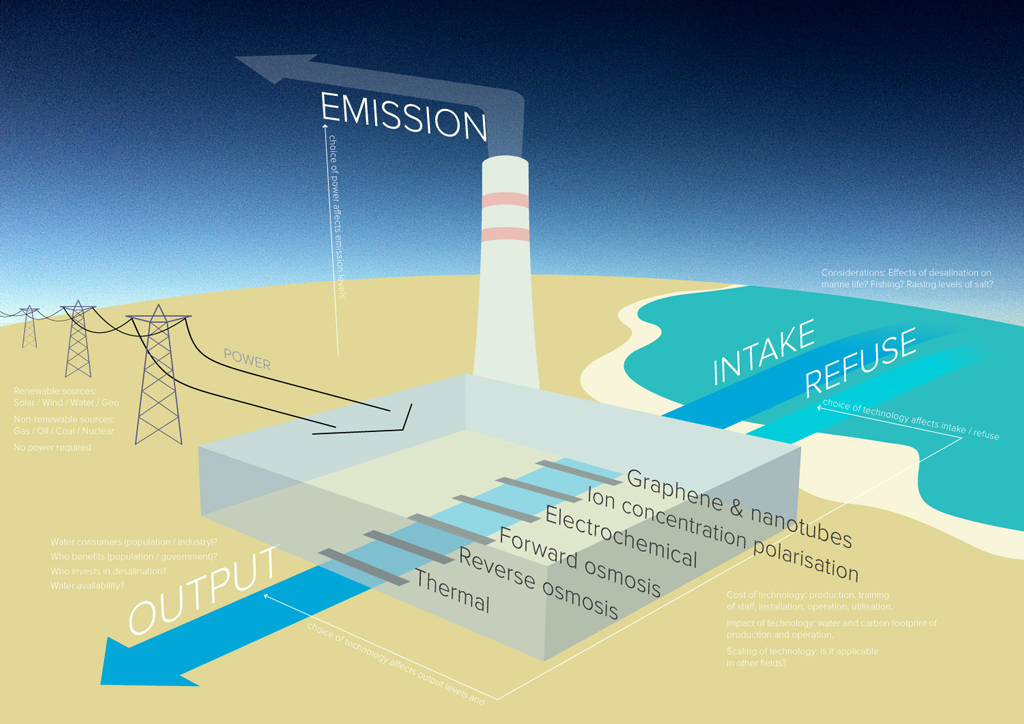

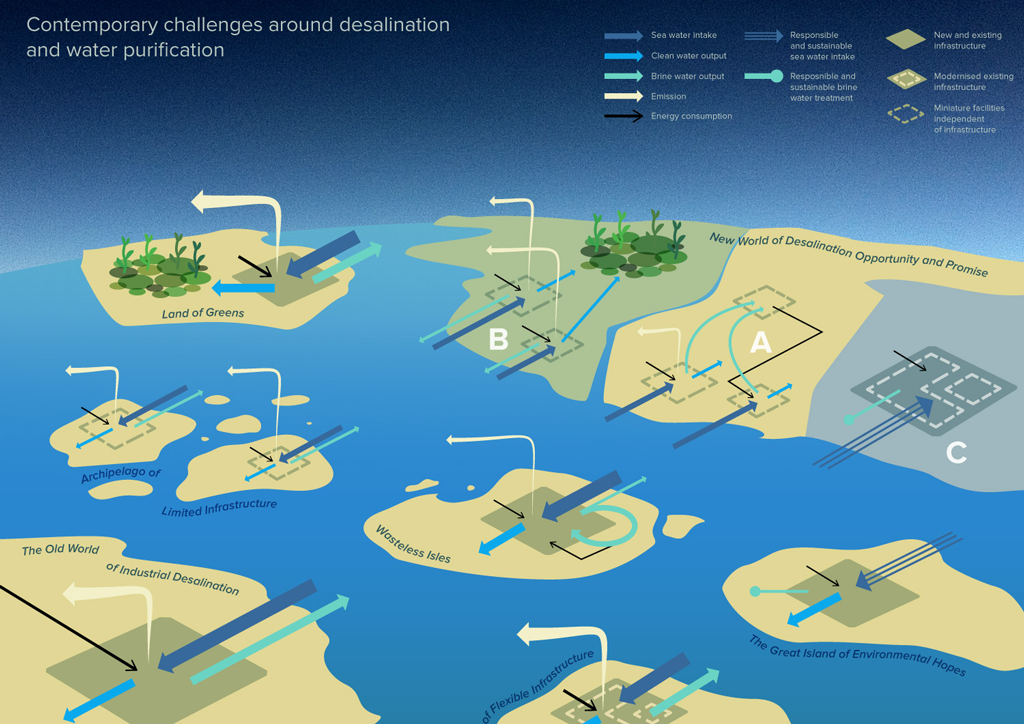

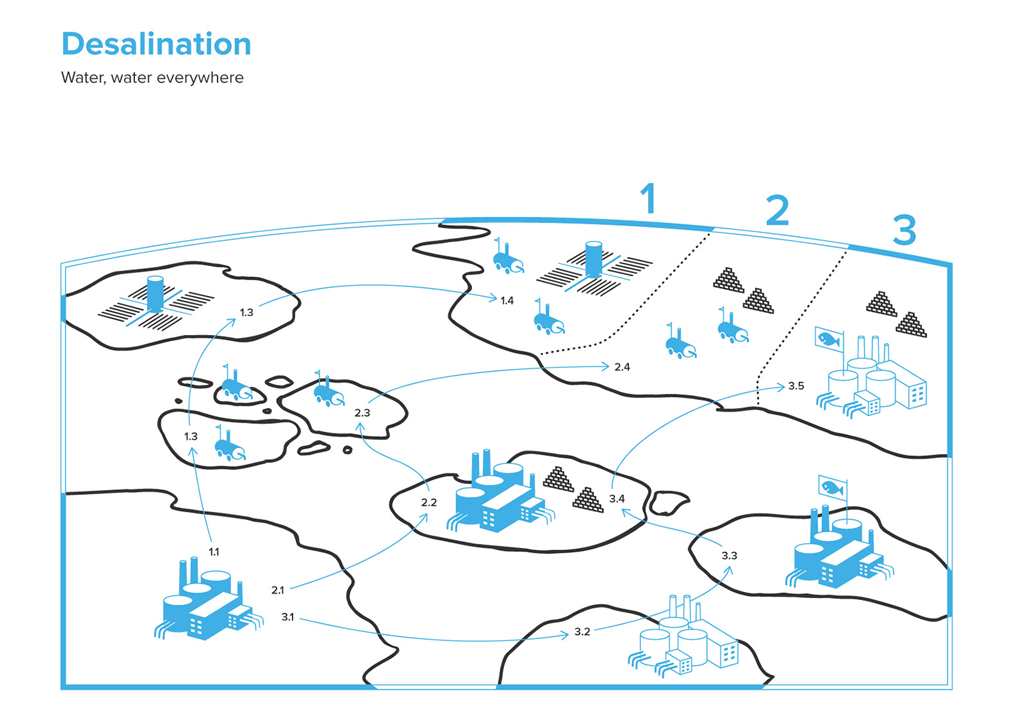

As with a map of a physical landscape, ‘challenge maps’ - as we started calling them, described the barriers to be overcome or circumnavigated, promising pathways to a goal, and the milestones along the way. The maps aimed to translate the scientific, technical, and social factors surrounding a challenge area into an imagined landscape.

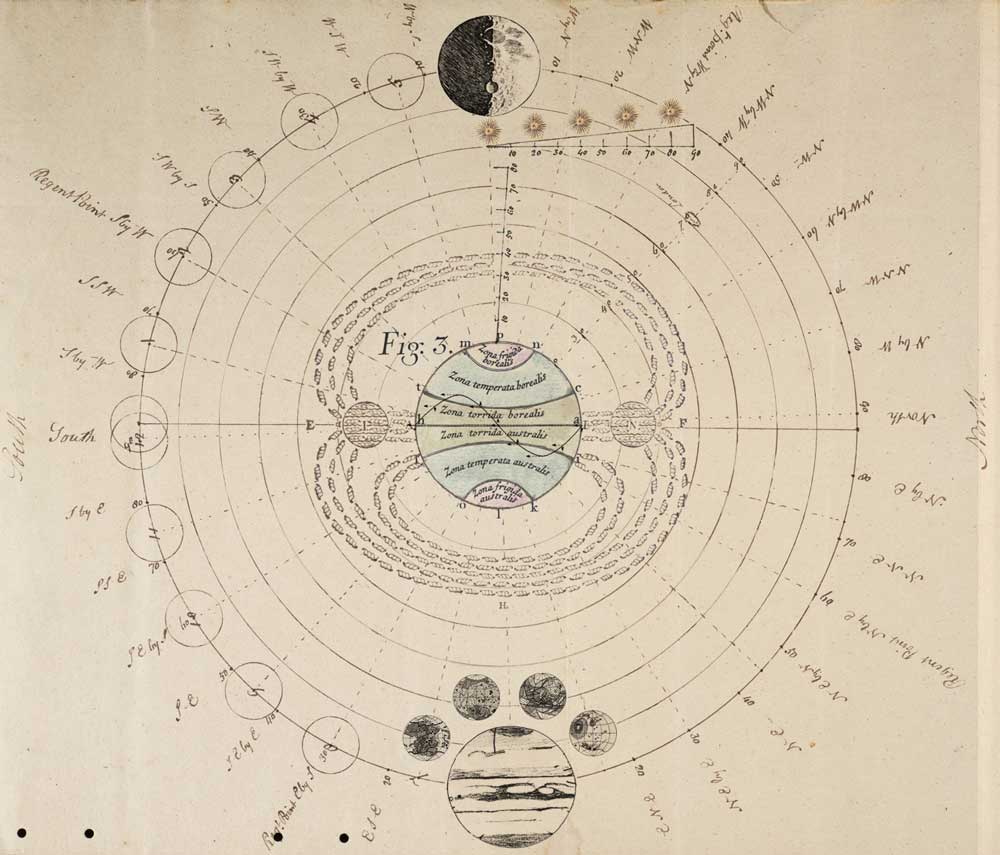

Before we started work on Longitude 2014, we decided to see if we could make a map for the original Longitude Act of 1714:

We put together this map to illustrate some of the potential solutions to the Longitude problem from the perspective of a natural philosopher in 1714. Elements of the map have been sourced from the fascinating collection of Papers of the Board of Longitude archived at the University of Cambridge.

The main aim of challenge maps wasn’t to achieve accuracy, but to become a starting point for conversations with experts. We wanted them to be engaged in the research process, explore alternative solutions, and play an active role in shaping the landscape defining each challenge area.

Challenge Maps in Practice

One of the first things we learned was that representing a challenge topic as a two dimensional map didn’t always work. Some topics were simply too complex, especially when cultural and political factors needed to be represented. The Food and Dementia topics were certainly the most difficult. For the Water, Flight, Paralysis, and Food challenge topics, however, the approach seemed quite natural.

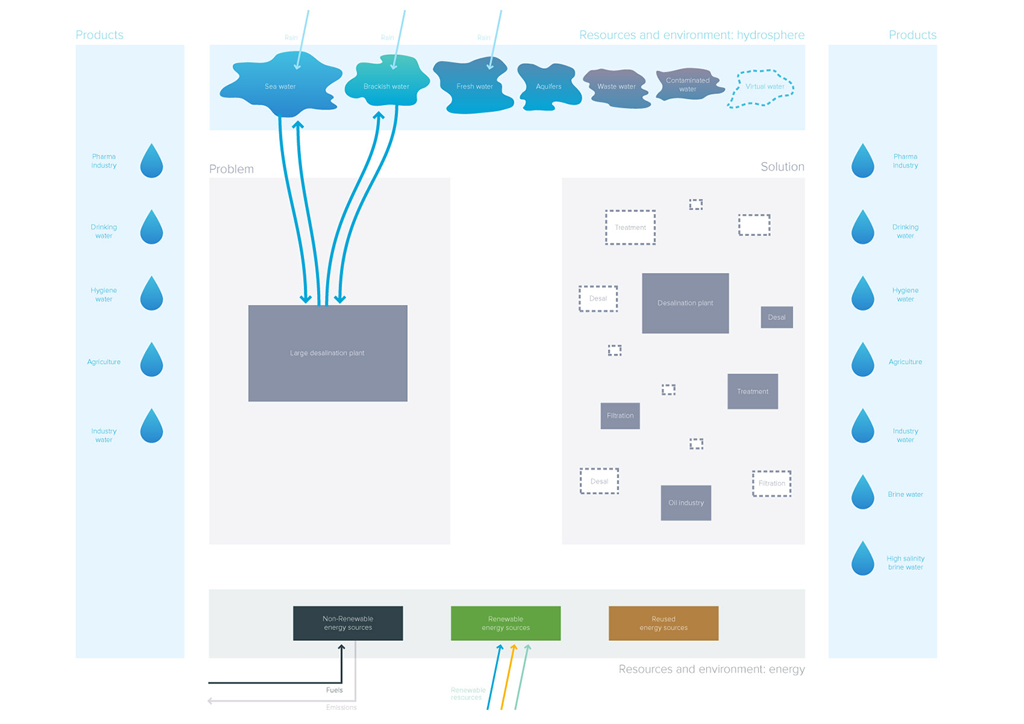

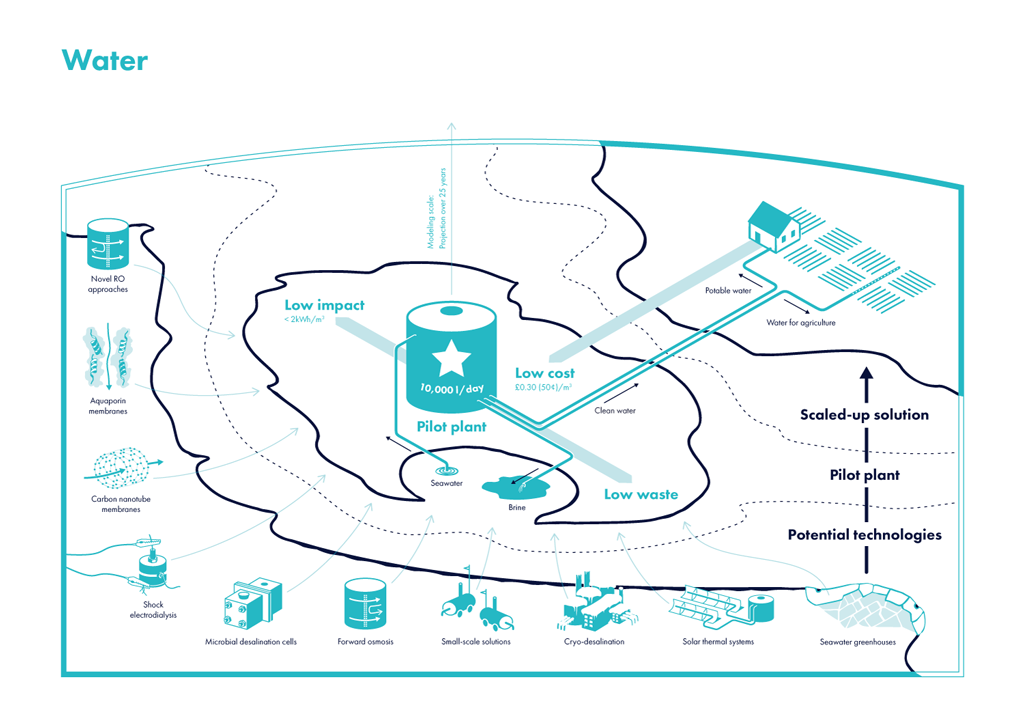

Successive iterations of the challenge map for the Water prize

Used as research stimulus in interviews with experts, the maps triggered different responses. While some experts found them very helpful and used them to build their arguments, others criticised or simply ignored them. We tried to make sense of each of these reactions to further develop our understanding of the six challenge areas.

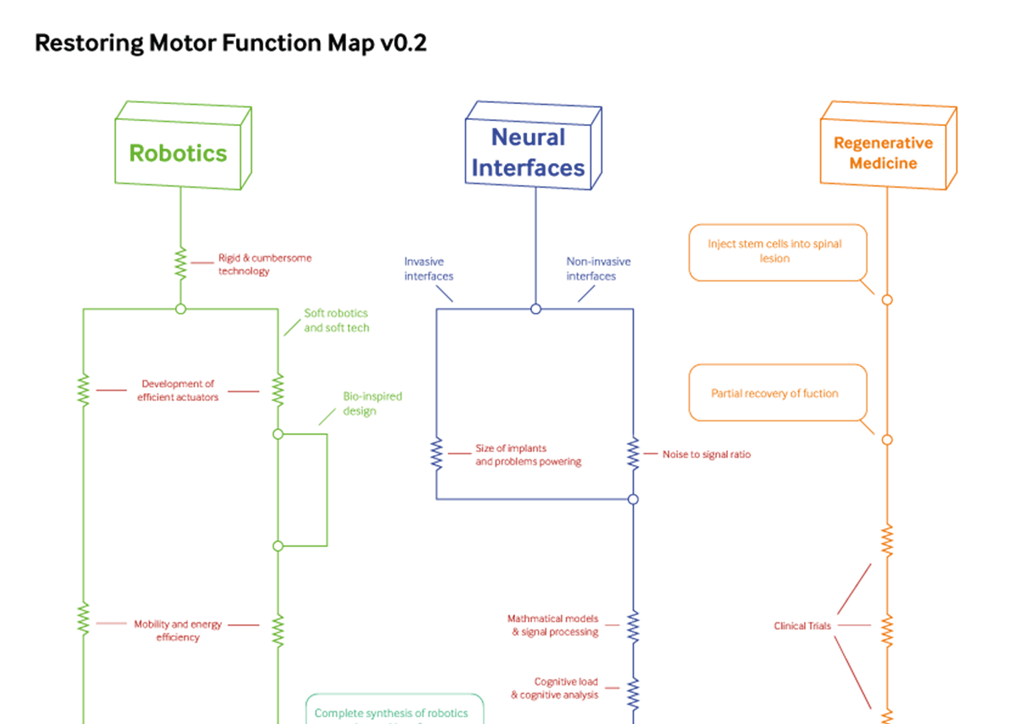

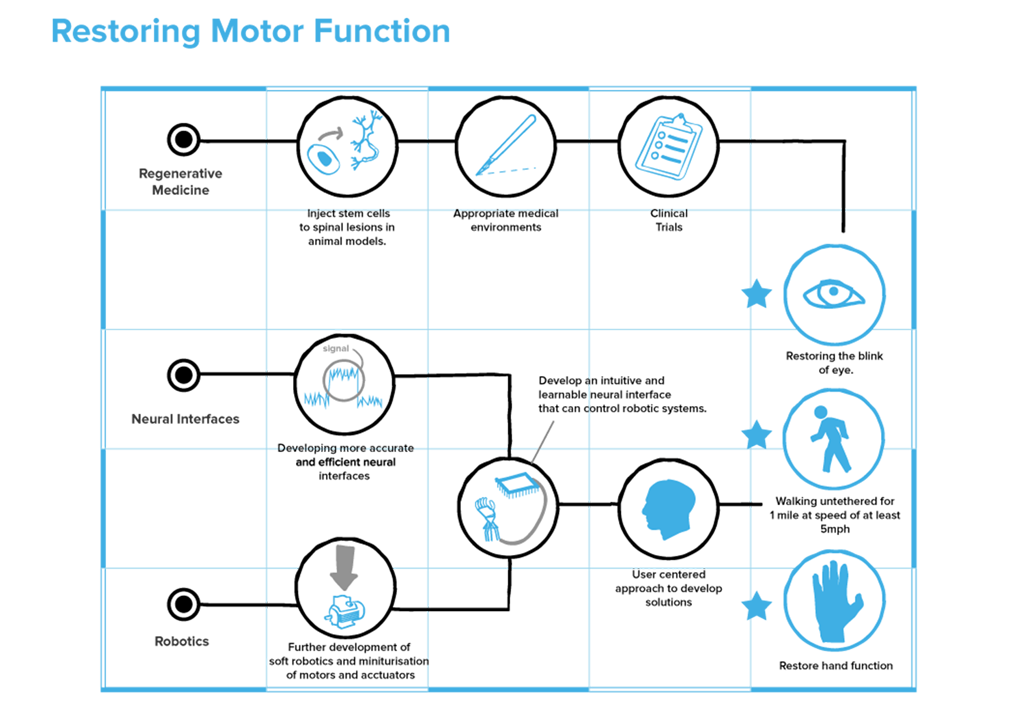

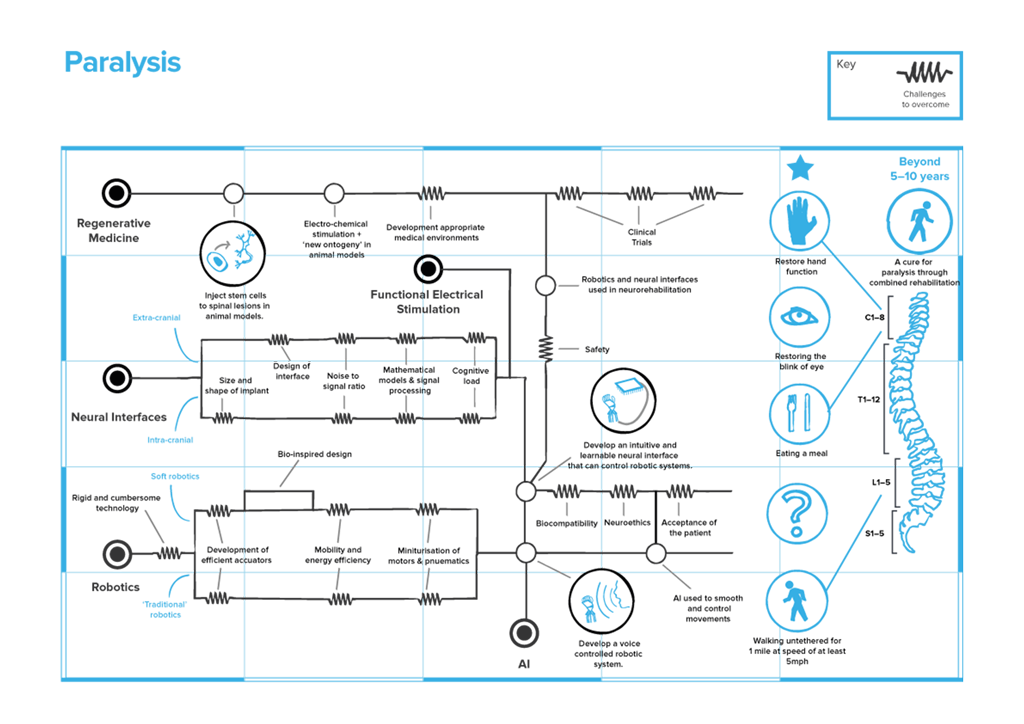

Successive iterations of the challenge map for the Paralysis prize

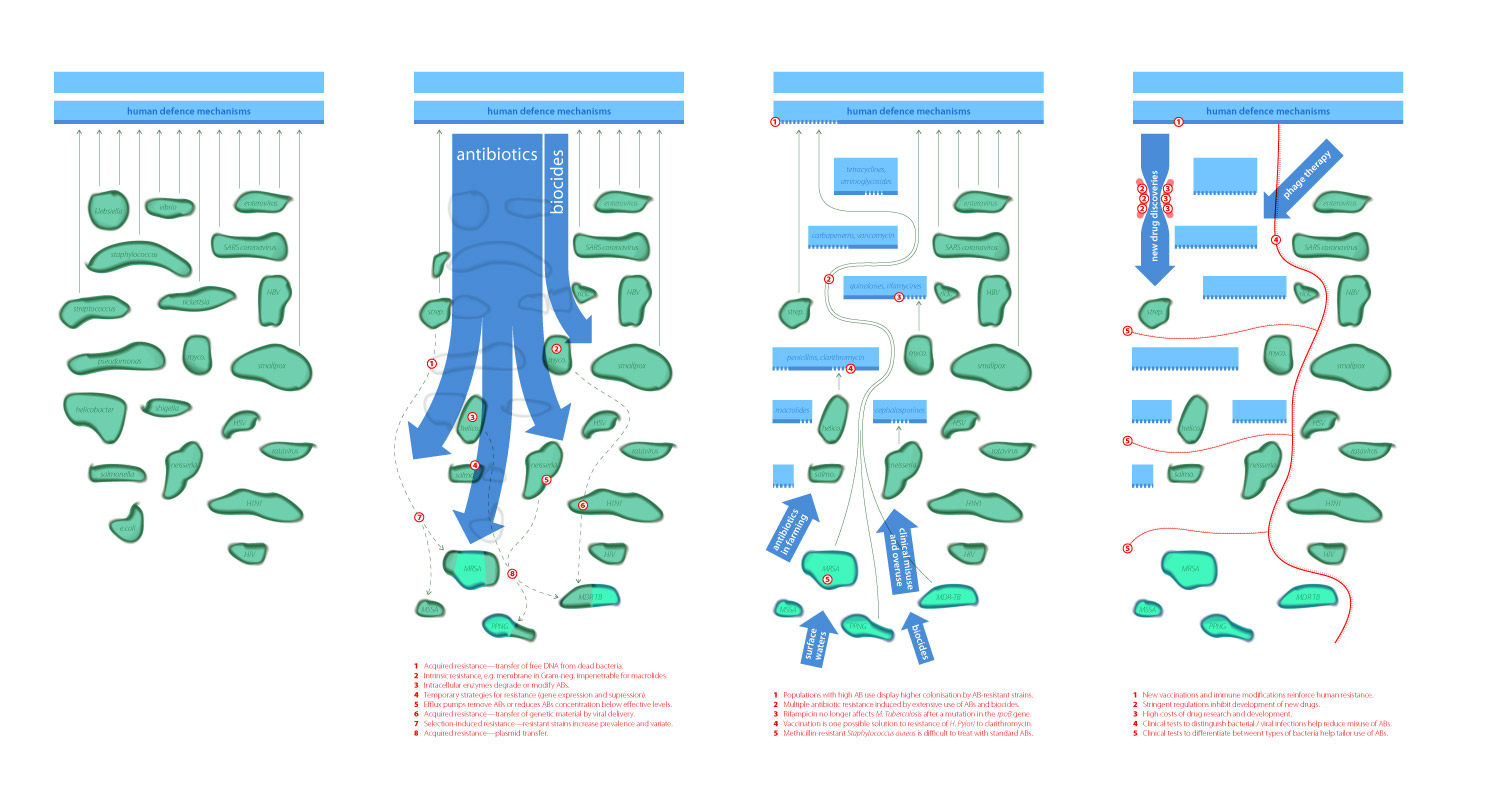

As well as helping us develop our factual understanding of the challenge topics, we would often receive some surprisingly nuanced feedback. In early drafts for the Antibiotics challenge map we represented the history of infection control as a war between two opposing armies: microbes and humanity. This war metaphor appears regularly in the literature and popular press so it seemed sensible to appropriate it for our challenge.

First version of the challenge map for the Antibiotics prize

However, when presenting this map to experts they reacted strongly against it, arguing (rightly) that the war metaphor plays a role in shaping people’s attitudes towards bacterial infections and helps to propagate the irresponsible use of antibiotics.

Final version of the challenge map for the Antibiotics prize

Maps allowed us to set a frame around the challenge area without actually imposing any direct constraints on what could be included. Elements of the map, such as the relative position of objects or landmark features such as bridges or rivers, became signifiers for barriers or opportunities for innovation in the challenge area. By encouraging interviewees to edit the maps we not only received information about potential fields or technologies which could generate solutions, but also contextual information about the likelihood of their success or ability to be attained within the lifetime of the Longitude Prize.

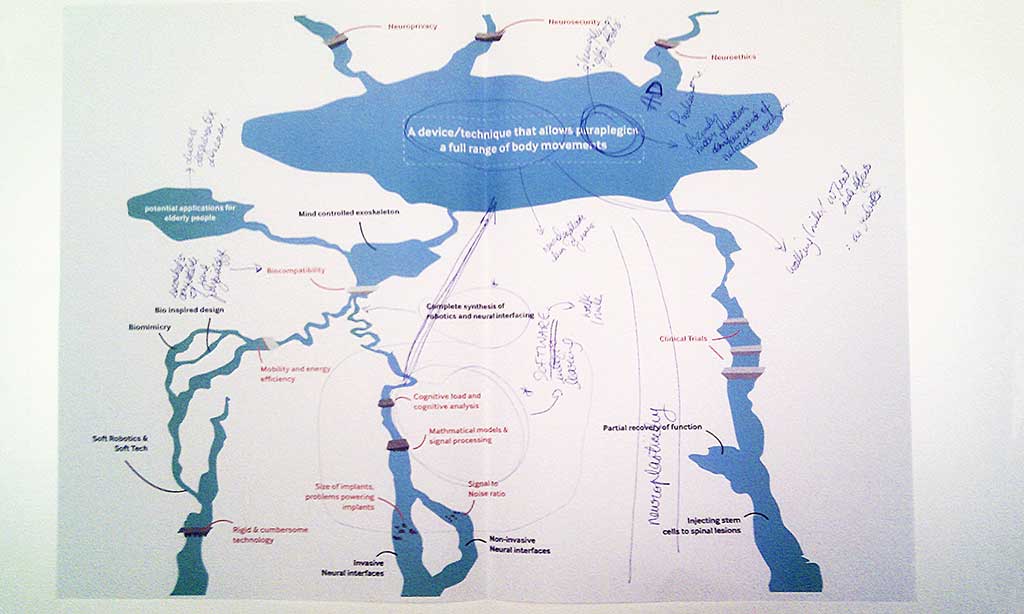

An annotated challenge map for the Paralysis prize following an interview with an expert in the field

Synthesising Expertise

Seven weeks and 60 interviews later, we ended up with six very different challenge maps. While some developed along the initially defined structures, others were redrawn into completely different shapes as our understanding of the challenge areas changed. Some maps were quite clear and concise, others were still rather abstract or cluttered - making plain the issues in need of further research.

All six Longitude challenge maps

Although the maps themselves evolved through this process, they are actually more of a byproduct. As research stimulus, they enabled us to have guided yet flexible conversations with experts, encourage them to explore novel technologies, and suggest potential pathways to solutions.

The next step for us was to build on these conversations and start shaping the basic structure of the six challenge prizes. This became the challenge prototyping phase of the Longitude project, which we will discuss in our next post.

In February 2014 we started work on the Longitude Prize. How we approached this project and what we learned along the way is the topic of the following posts:

A challenge prize is a very simple idea. A problem is identified and publicised along with the offer of a reward to the person or organisation who can find the first or best solution. Identifying the problem, however, is a challenge in itself.

A challenge fit for a prize

When we started working on the Longitude Prize in early 2014, the term ‘challenge prize’ was unfamiliar to us. Yet we resonated to the underlying concept – engaging with experts to design competitions that could advance scientific inquiry and, hopefully, the discovery of solutions to some of the world’s most pressing problems.

One of the first things we learned while working on Longitude was that not all problems can be made into good challenges. The problem identified for a challenge prize needs to be:

1. Simple to understand and articulate

- It is very difficult to publicise a challenge that is too complex to be described succinctly and clearly.

2. It has to be a real problem, not a manufactured one

- It is very easy to be drawn to what look like real problems, only to find that they are in fact artificial problems based on too many assumptions.

- This becomes especially treacherous when researching problems faced by people in other geographies and cultures.

3. There need to be people interested in solving it

- A good challenge prize will galvanise a community of people who have been thinking about the problem for a while.

- A challenge prize is open to everyone, but if no-one sees themselves as the right person to solve it, setting a challenge will have little benefit.

4. It has to be soluble

- The challenge must not require a change to the basic laws of physics in order to solve it (we fell foul of this a few times).

- This consideration is especially relevant for prizes that aim to encourage innovation in mature fields of engineering like aviation and water processing, where the temptation might be, for example, to demand impossible reductions in energy usage.

- A problem might be too culturally or politically complex to be able to benefit from a technological solution.

5. It can’t have been solved already

- You don’t want to open up a Challenge Prize only to find that it has already been solved by a team of researchers you weren’t aware of.

We were given six broad challenge areas: Antibiotics, Dementia, Flight, Food, Paralysis, and Water. As our involvement in the project grew, our task became that of crafting good challenge prizes out of these areas.

Valuing expertise

We are not experts in any of these fields but we were lucky enough to work with expertise sourced from an international group of advisors. What we needed was an understanding of the key challenges within these areas, the likely areas of opportunity, and the motivations of potential participants in the challenge.

The Longitude Prize Journey

Our work on the Longitude Prize 2014 ended up being divided into three stages: challenge mapping, challenge prototyping, and challenge reporting. In the upcoming Longitude posts we will explain these phases individually to illustrate some of the materials used, their application in practice, and their outcomes.