In February 2014 we started work on the Longitude Prize. How we approached this project and what we learned along the way is the topic of the following posts:

In our previous Longitude Prize post we introduced challenge mapping which was our process for gaining enough understanding of the six challenge areas to start designing the challenges themselves. This post is about prototyping and testing different formulations for each challenge.

Similar to the previous research phase, we could only do this by talking to experts. This time around, we wanted them to think like competitors. We needed to understand whether the challenges we were proposing were right. Would they inspire healthy competition and novel solutions from a wide field of participants? Were they good problems?

Before we started the next round of interviews we wanted to create a proposal to stimulate discussion. So we came up with something called a challenge prototype.

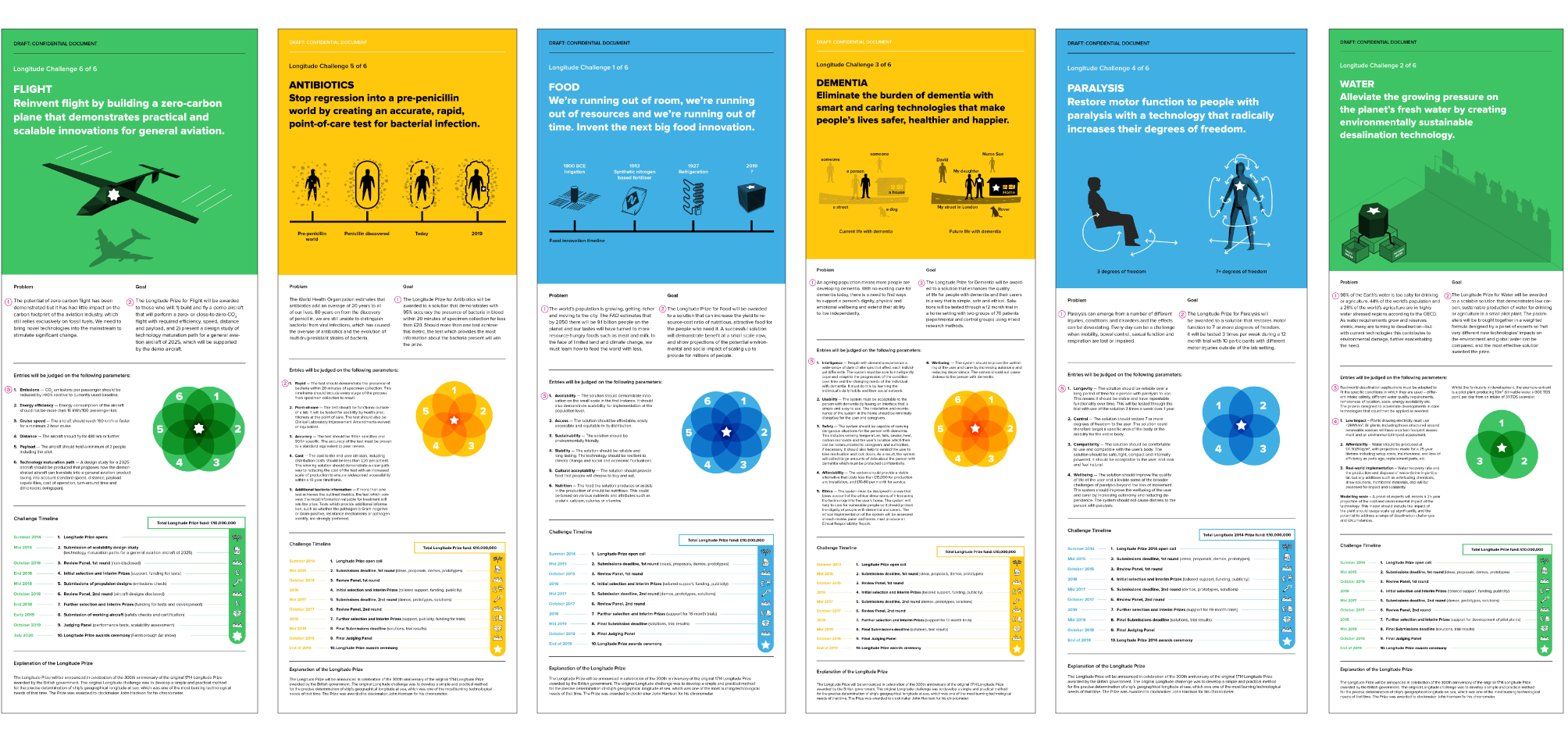

The structure of a Challenge Prototype

Despite the fancy name, challenge prototypes are pretty simple, one-page documents which summarise a challenge. They state the vision of the challenge, define the problem to be solved, set the goal to be attained, detail the judging criteria and, lastly, spell out the logistics of taking part: deadlines and prize money.

All six Longitude challenge prototypes

By talking through these prototypes with experts we wanted to validate the conclusions we drew following the challenge mapping phase as well as get a better understanding of how competitors would approach such a prize. We wanted to move from the hypothetical to the concrete and get into the details.

Understanding competitors

Each interview started with the problem and goal statements in the prototype. When an expert disagreed with the proposed challenge, discussing these two statements helped us understand whether this was due to our framing of the problem, or the solutions we were expecting.

The most detailed conversations generally took place around the judging parameters and timelines. We wanted to know whether the judging criteria made sense and whether they were objective enough for solutions to be assessed against them. Equally important, we wanted to know if the challenge had a reasonable chance of being solved in the given timeframe and understand what kind of support could motivate and encourage innovators along the prize journey.

Stating the judging criteria with specific targets and limits - even if these weren’t necessarily the right ones – helped engage experts in detailed conversations around what form potential solutions might take and how they could be assessed. This allowed us to get a feel for the dynamics between the individual criteria and how they fit together.

One of the unexpected benefits of having the challenge written down were the corrections we received to our (often clumsy) use of specialist terminology. These are the types of mistakes that don’t get picked up in conversation, but stood out to experts on paper.

The last question we asked the experts we interviewed was whether they would take part in the challenge as described. If the answer was ‘yes’, then this was a positive sign that we were getting close. If the answer was ‘no’, then this was a good opportunity to ask why.