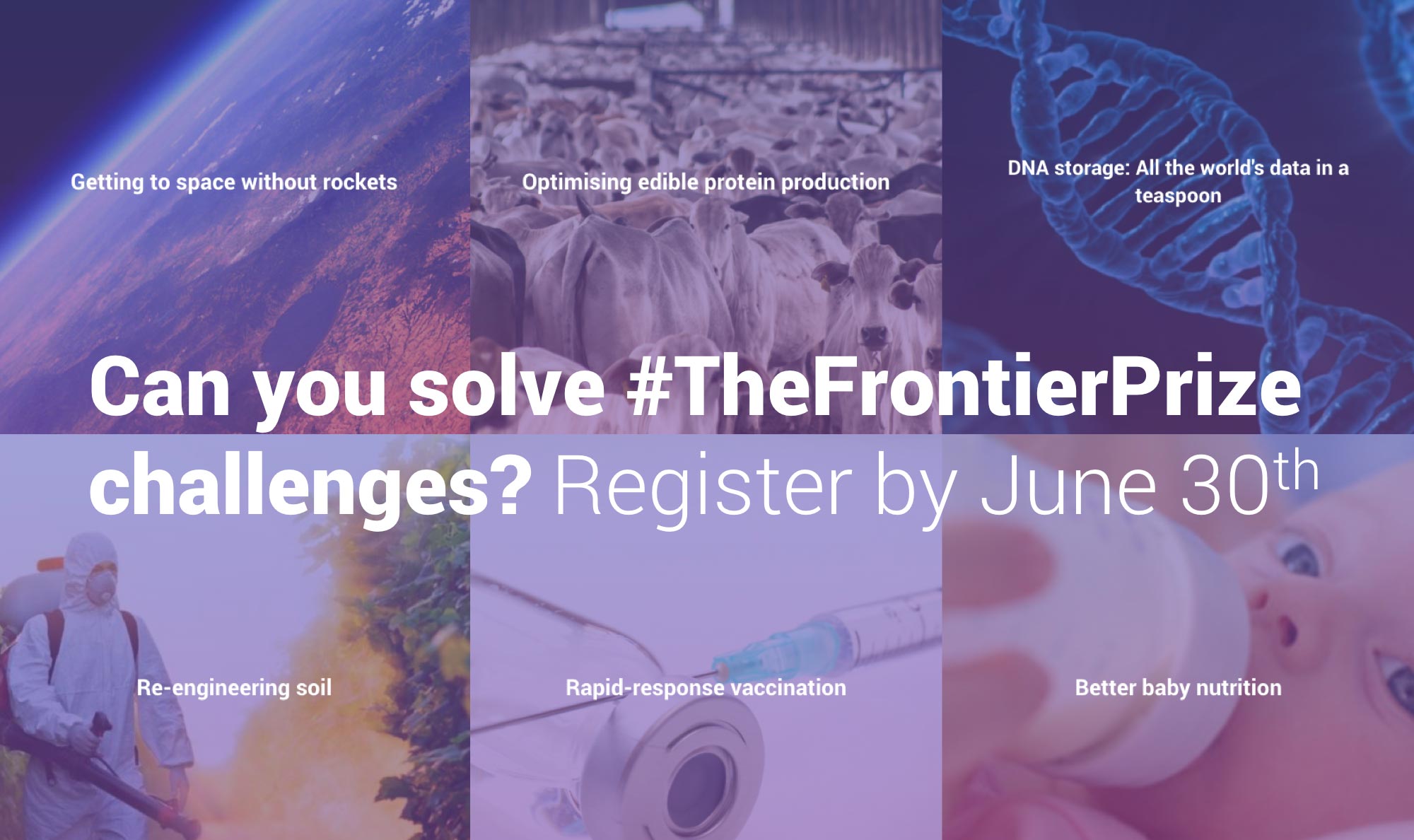

We’re excited to announce the launch of The Frontier – the world’s first venture-focused challenge prize! The prize is aimed at bringing together scientists, engineers and industry experts from all over the world to solve specific technical challenges.

The Frontier is launched by Hello Tomorrow, a global non-profit supporting science driven innovation, and developed by Deep Science Ventures (DSV), a VC backing scientists. DSV have allocated up to £500k in available prize & investment funding to successful applicants.

The Good Problems team at Science Practice will be working together with DSV over the next month to define specific technical challenges within three of the six high level challenge areas – optimising edible protein production, re-engineering soil, and better baby nutrition.

All six of the Frontier Challenges.

Scientists, engineers and other technical background individuals from all over the world are encouraged to apply and work together on solving specific technical challenges in the 6 highlighted areas. Applicants will have 30 days to form teams online and work on developing solutions. 30 successful teams will receive online support and mentorship from DSV and 10 will get to pitch at the Hello Tomorrow Global Summit in Paris, 26-27 October 2017, in front of a top lineup of VCs and over 3,000 science influencers.

We’re really excited to be collaborating with DSV on the design of the Frontier challenges and we look forward to seeing the emerging ventures!

If you want to start your own business, have a STEM background and are intrigued by one (or more) of the Frontier challenges, make sure you sign up by the 30th June!

In September last year a new issue of the 2+3D Design Magazine came out and inside it — we had written an article introducing the three Science Practice teams. 2+3D is the biggest design magazine in Poland. The article was titled ‘Wieloboje w projektowaniu’ which in English translates to ‘Combined Track and Field Events in Design’ — a reference to the very interdisciplinary nature of our work at Science Practice, where it is not uncommon to see designers and researchers working together with geneticists, developers, science writers, illustrators, agriculture experts, aeronautics engineers, filmmakers, policymakers, data scientists… In fact — each project we work on at Science Practice requires a unique blend of expertise.

New issue of 2+3D Design Mag came today and inside... a 4-spread article about our three teams https://t.co/d8vD5IGhdZ by @marekkultys pic.twitter.com/CbeNRkMQqx

— Science Practice (@sciencepractice) September 26, 2016

The word spread fast and not long after the publication of the article I received an invitation from the organisers of World Usability Day WUD Silesia to talk about our work at Science Practice at their conference in December 2016 in Katowice, Poland. I always enjoy such invitations, as they are usually a nice opportunity to look back at projects from a different perspective and see how they resonate with people. And because the team of the WUD Silesia conference was ‘Sustainable Development’, I immediately thought about our Good Problems team.

In 2016 most of our work in the Good Problems team was focused on problems in the humanitarian emergency sector (namely, the WASH and GBV projects). Humanitarian aid is often defined in contrast to development work. Humanitarian actions are usually seen as short-term interventions (days, weeks or months) focused on the needs of people directly affected by a crisis. While the need to integrate sustainable principles in humanitarian aid is part of a growing trend in the sector, I realised that we had another project in our portfolio that was strongly rooted in the sustainable development context – this was the Longitude Prize 2014.

Sustainability and the Longitude Prize

The Our Common Future report completed by the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987 defines sustainable development as:

Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Central to sustainable development are two concepts:

-

the concept of needs;

-

the concept of limitations.

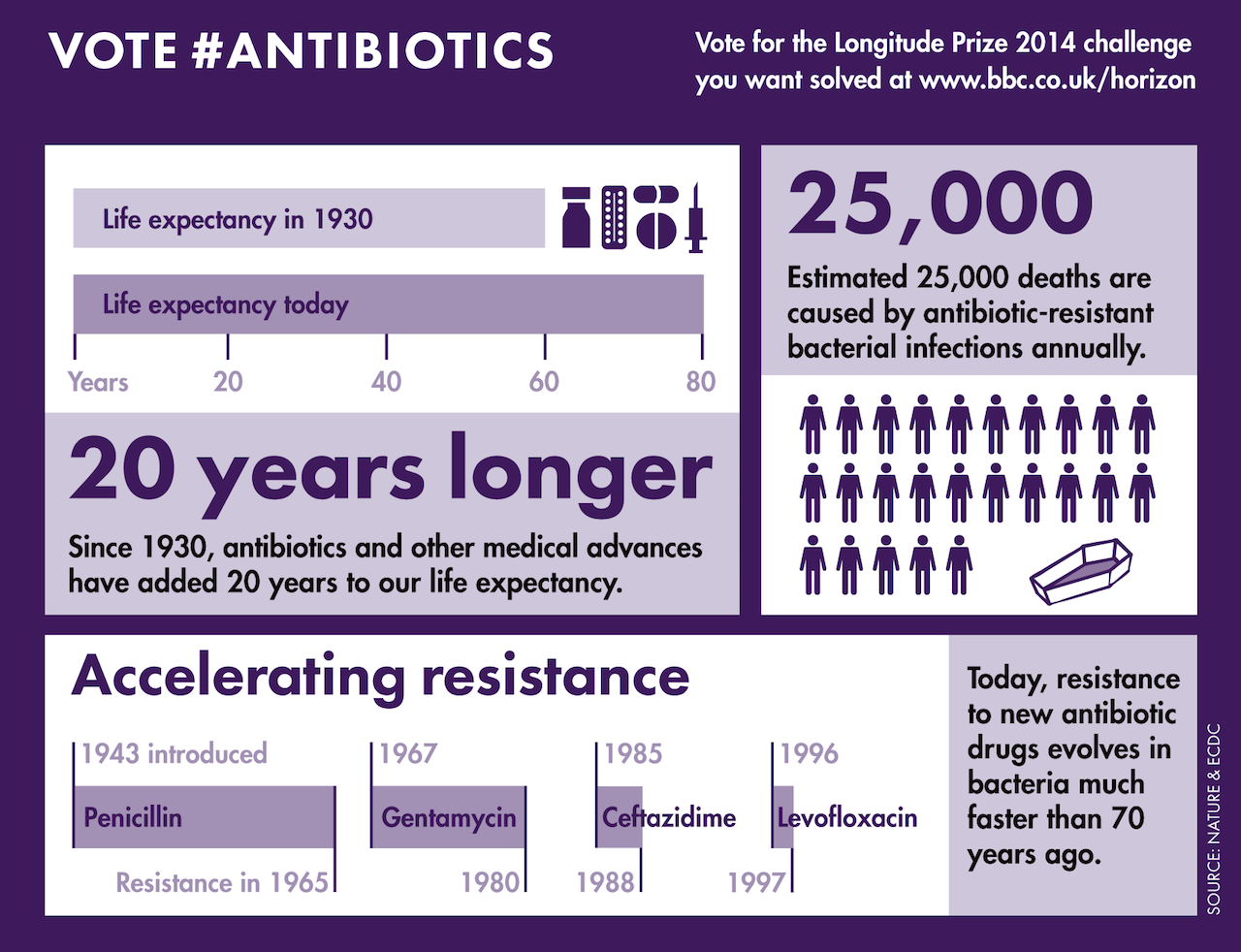

As we developed prototype challenges for each of the six candidate topics for the Longitude Prize 2014 (Antibiotics, Dementia, Flight, Food, Paralysis, and Water), it became increasingly apparent that most of these problems stem from our inability to sustain a technology or a service that we already enjoy into the longer future. Simply speaking — our current situation is unsustainable and unless we come up with something really good, we won’t be able to enjoy those technologies and services for much longer.

The Antibiotics candidate provides an illustrative example. Here, the problem we are facing in terms of sustainable development can be phrased in this way:

How do we keep the benefits of using antibiotics today, and not risk future generations’ right to benefit from using antibiotics in the future as well?

With this phrasing the concepts of needs and limitations can now be clearly defined:

-

our need is to be able to use antibiotics effectively;

-

future generations’ need is to be able to use antibiotics effectively in the future;

-

one limitation is that the more liberally we use antibiotics, the less effective they become (due to evolving microbial resistance);

-

another limitation is that the development of new antibiotics becomes ever more difficult and expensive, as it takes ever less time for bacteria to develop resistance to a new drug.

Longitude Prize 2014: Antibiotics infographic. Key things you need to know about the importance of the problem of rising antimicrobial resistance. Presented data put the needs and the limitations into a quantifiable perspective.

In June 2014 BBC announced that Antibiotics had been selected by the British public to be the final topic of the Longitude Prize 2014. In conclusion of over 6 months of our research and design work for the Longitude Prize, we proposed that the Antibiotics prize should focus on improving antibiotic conservation through better stewardship of the existing antibiotic treatments. This in practice could be enabled by a new point-of-care diagnostic that should help clinicians target antibiotic treatments more effectively. The challenge statement in the Longitude Prize rule book reads:

The Longitude Prize will reward a competitor that can develop a transformative point–of–care diagnostic test that will conserve antibiotics for future generations and revolutionise the delivery of global healthcare. The test must be accurate, rapid, affordable, easy–to–use and available to anyone, anywhere in the world. It will identify when antibiotics are needed and, if they are, which ones to use.

The competition is still running.

Interestingly, other candidates that did not become the topic of the main Longitude Prize 2014 competition were also rooted in long-term sustainability context. The goal of the Dementia challenge was to address the challenge of caring for a growing ageing population while relying on finite human and financial resources. The Food challenge was focusing on the need to produce more food to feed a growing population on one hand, and on the limitations of agriculture’s growing environmental impact on the other. The Flight challenge was looking for a breakthrough that would balance our need for a rapid and convenient means of global transportation with the limitations posed by environmental impact of aviation’s CO2 emissions.

To feed the future, we need to make changes today - vote #food for #longitudeprize: http://t.co/O2bXDYkMiy pic.twitter.com/c6E2VQbG2R

— Longitude Prize (@longitude_prize) June 11, 2014

5.7 billion journeys a year - #flight may be vital to our economy, but how do we make it sustainable? #longitudeprize pic.twitter.com/aH31p0m3lg

— Longitude Prize (@longitude_prize) June 18, 2014

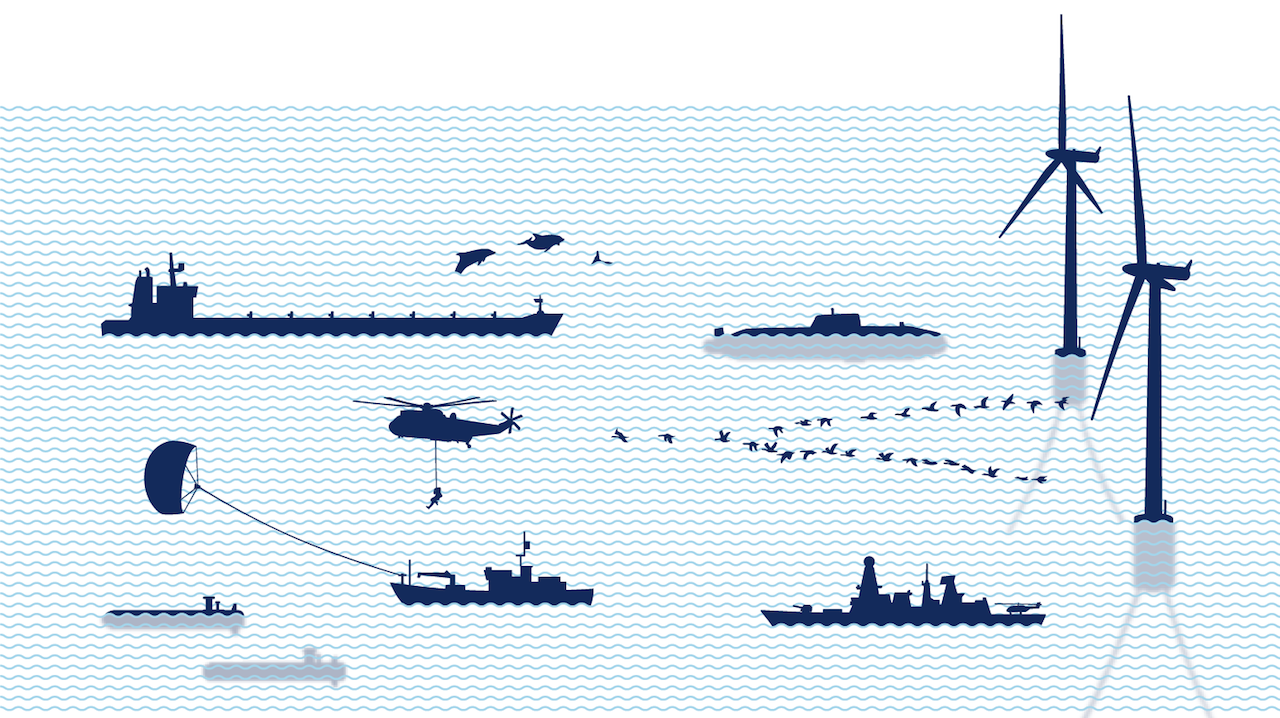

Working with the UK Government Office for Science to research and visualise UK Sea Governance.

Connecting scientific evidence to policy-making is a non-trivial process. Evidence can be conflicting, incomplete, or inconclusive, obscuring the ability of policy-makers to apply this information. Likewise, policy-makers may not be receptive to information, or can be constrained in the choices that they are able to make. More than this, scientific evidence almost never compels any particular policy direction, rather providing insights into potential benefits, costs and risks of action. This difficult but important relationship is well recognised by UK Government, with many organisations in place to help facilitate conversation between researchers and policymakers.

One of these organisations is the Government Office for Science (GO-Science), who make sure that UK government departments have access to scientific advice and evidence to inform their policy-making. An important part of this is the Foresight programme, which looks forwards to identify opportunities and challenges that might affect the UK in the near future. Every year GO-Science chooses 2 or 3 different topics to investigate, producing a report and raising awareness of how government could use evidence to positively influence the UK.

One of Foresight’s most recent projects is ‘The Future of the Sea’, which is due to be published this year. The project is looking to understand the ways in which the UK interacts with the sea, how that might change in the future and how Government can act to sustainably support the people, organisations and industries involved.

Early in the project GO-Science approached us to understand if we could work with them to organise and rationalise their initial research, and to design a stimulus that visualises the responsibilities of different UK Government departments and agencies in relation to the Sea. The idea being that by synthesising and presenting research in an engaging and accessible way, interactions between foresight researchers and policy-makers would be more focused and fruitful, easing the relationship between policy and evidence.

How does UK Government interact with the sea?

Our starting point for this work was the initial research that GO-Science had done into the different interests that the UK has in the sea. This includes a diversity of concepts such as maintaining biodiversity and supporting coastal tourism, marine industries, port infrastructure, shipping, and the development of new technologies for ocean mapping. All of these related but distinct interests needed to be represented, with meaningful links being highlighted wherever possible. As important was finding a way to represent the responsibilities of different government departments and organisations.

Our goal was to produce something that would simplify the complexity of the interactions between people government, and marine, maritime and coastal activities without dumbing down or removing important detail. The aim was that this would facilitate conversations about how government is currently organised and how it could change, but also stand alone as a picture of UK sea governance.

Looking for an organising structure

Draft illustrations showing ideas for visualising links between concepts

We began by organising the interests into those that were more similar to one another or more different based upon different guiding principles. For example we experimented with grouping by the geographical location of the interests - in, across or by the sea. Another principle was the intended purpose of the interest such as extracting resources, or protecting biodiversity. We then drew and defined connections between groups, such as dependencies or beneficial relationships.

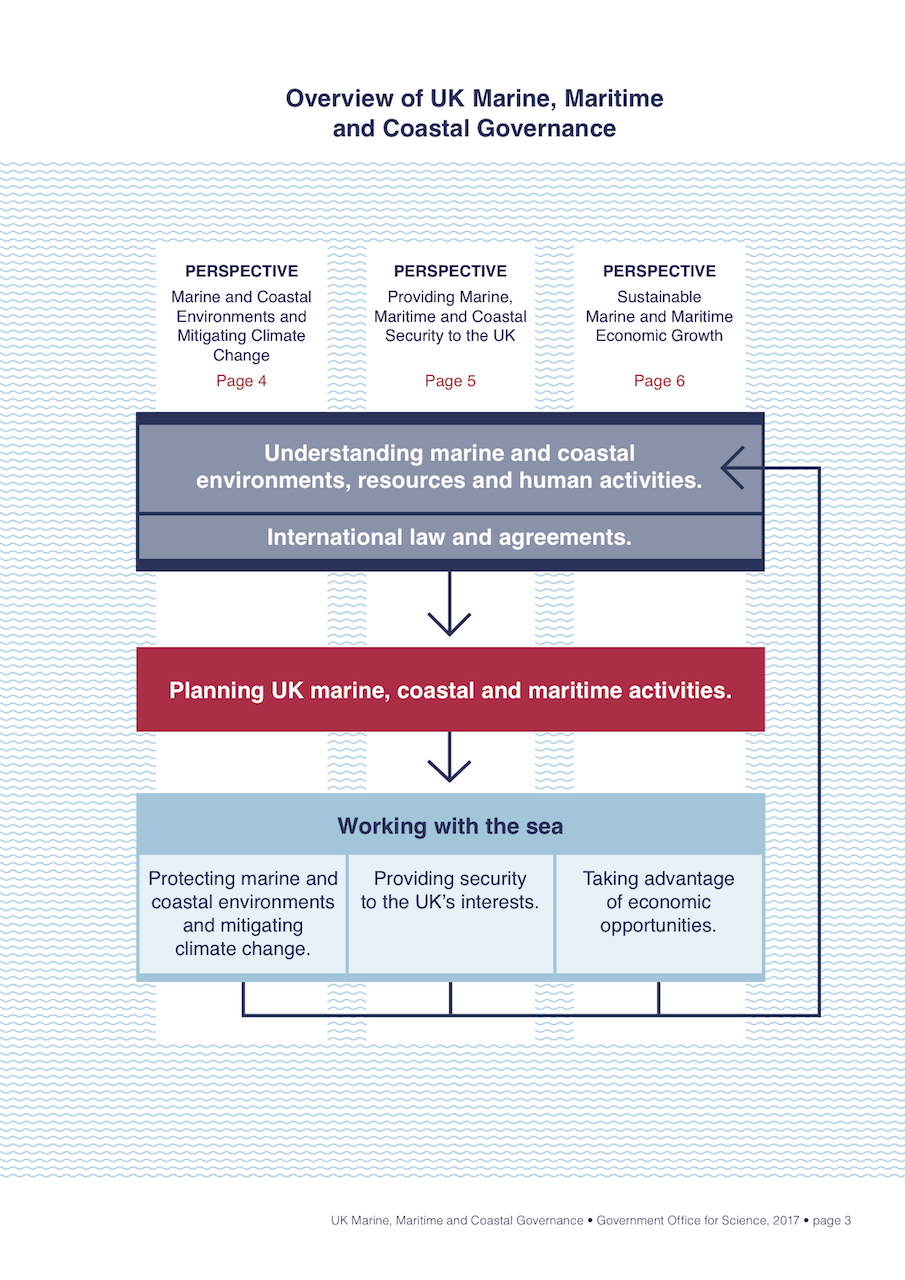

After a few iterations trialling out different organising principles, we decided with GO-Science to use a simple structure based around a flow of interests grouped into understanding, planning and working. Each group is dependent on the activities of the previous one.

-

Understanding — Interests with a purpose of monitoring and research on the sea, coastal and marine environments, climate or human activities related to the sea. These activities also include efforts to analyse this data.

-

Planning — Interests related to planning and regulating economic, environmental or security activities based upon the information gathered in ‘Understanding’.

-

Working — Diverse marine, maritime and coastal interests to sustainably benefit from the sea, and to protect the UK’s ability to continue to do this. The flow begins once more as there are efforts to monitor and understand the impacts of these activities.

This structure allowed the UK’s interests to be described as collectively working towards one of 3 high level goals: Marine and Coastal Environments and Mitigating Climate Change; Providing Marine, Maritime and Coastal Security to the UK; and Sustainable Marine and Maritime Economic Growth. For each of these goals we produced a visualisation showing the major industries, regulations, departments and people involved.

We then tested out the diagrams with representatives from different government departments. Based upon their feedback we iterated and improved the designs. Most significantly we made sure that it was possible to use the three diagrams together to show a whole picture of UK sea governance.

Managing complexity

Cover and overarching structure from our Future of the Sea report

As our first experience designing a tool to facilitate science policy discussions, this project proved to be a really useful learning experience for us.

Government is an enormous and complex organisation, with numerous ways of dealing with cross departmental topics such as the sea. To have a full understanding of this requires significant effort. We found that attempting to communicate this visually can serve a useful purpose in helping people to access the topic, and to discuss ways in which governance can be proactive to future challenges and opportunities.

One of the biggest challenges was in pitching the level of detail correctly. Different departments have different levels of interaction with the sea, as well as different understandings of whose responsibility certain activities are. It is likely near impossible for a representation to be perfect from all perspectives.

We found that it is precisely this difference of opinion that this type of work can help to bring out in the open. The process of presenting people with a picture of what we thought they and others do resulted interesting discussions around governments role in the sea. The diagrams give people a chance to react to something, focusing discussion and highlighting opportunities for relationships between departments.

This blog post is part of a series on our Good Problems team. Each post looks at a different step in the process of designing a funding programme and makes suggestions about how to optimise to achieve a greater impact.

How do you bring problems and solvers together?

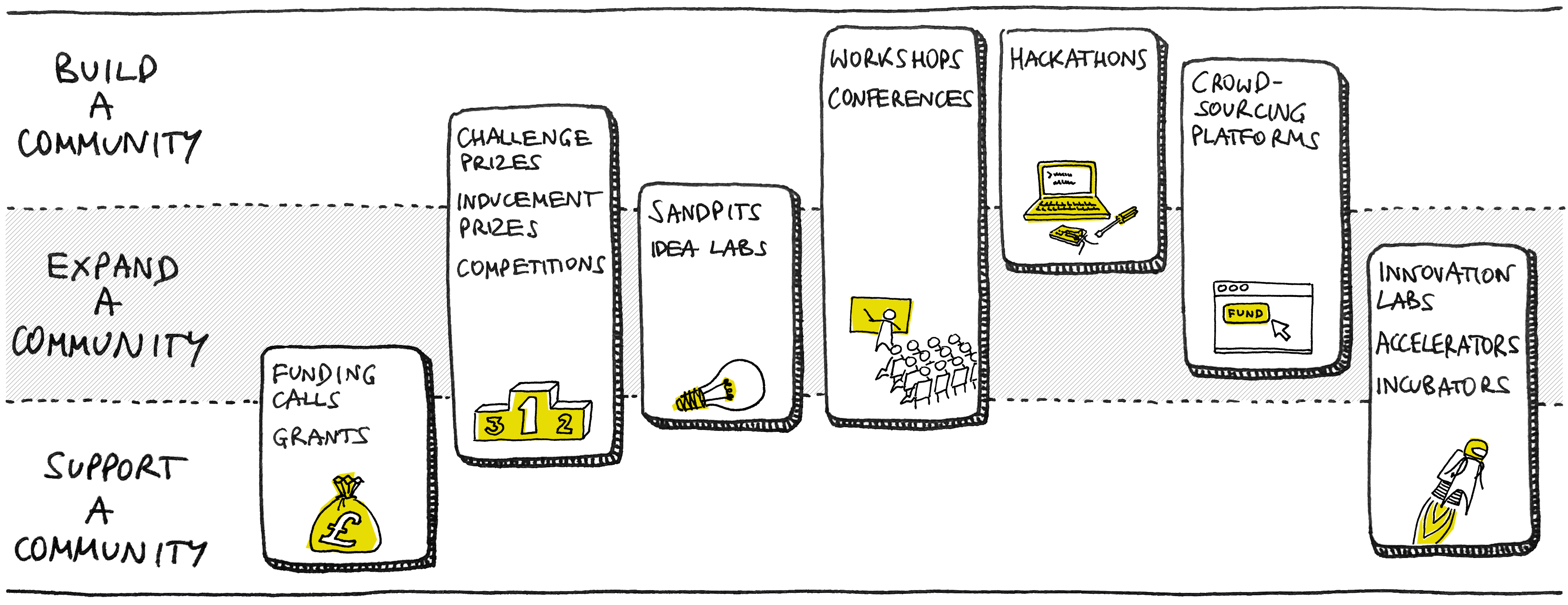

If you work at a funding organisation, this question should be familiar to you. Do you set up a funding call, launch a challenge prize or run a hackathon? Do you hold a workshop to familiarise people with the problem or use a crowdsourcing platform to reach a broad range of potential solvers?

In the first post of the series we talked about the advantages of identifying a good problem. In the second post we looked at the added value of understanding the skills, resources and motivations needed to solve the problem. This third and final post is about using this knowledge to design a suitable incentivisation approach.

There are many ways to incentivise problem-solving. Some more common than others. The suitability of each approach will depend on the problem and the community of solvers.

Challenges and Hackathons and Sandpits – Oh, my!

An incentivisation approach is a way of trying to motivate and support people to come up with solutions to a problem.

If people are not aware of the problem, they will need time to understand it and develop the motivation to work on solutions. If they are already working on solutions, they may need extra resources to achieve a breakthrough. That is why incentivisation approaches are so diverse. Here are a couple of examples:

-

Funding Calls / Grants: These are funding mechanisms that involve organisations offering financial support – and increasingly feedback and mentoring – to those interested in developing solutions to a specific problem. The problem can be defined either by the funder or the applicant (see the Humanitarian Innovation Fund’s open Core Grants or specific WASH funding calls).

-

Challenge prizes / Inducement prizes: These are prizes that offer a reward to the person or team who can first or most effectively meet a defined challenge. The prize can include a monetary reward, mentorship, or access to facilities and investors (see Nesta’s Challenge Prize Centre or InnoCentive).

-

Sandpits / Idea Labs: Sandpits (or Idea Labs in the US) are residential interactive workshops that bring together participants from across disciplines to work on addressing specific research challenges. The outcomes of a sandpit are not pre-determined, but are defined during the event (see EPSRC’s approach to designing sandpits).

-

Workshops / Conferences: These are a little bit different. While neither are funding mechanisms per se, they can help raise awareness of a problem and generate interest in solving it. Conferences tend to be larger and focused primarily on encouraging an exchange of ideas and forming new collaborations. Workshops can be more hands-on, with time allocated to working in groups to explore a problem and develop ideas (see our lessons from designing a workshop on Surface Water Drainage for the Humanitarian Innovation Fund).

-

Hackathons: Short and intense events where designers, developers, entrepreneurs and people with specific domain expertise collaborate on building projects that can help solve a defined problem (see Startup Weekend).

-

Crowdsourcing platforms: Online platforms where people can contribute with ideas, collaborate on projects, provide feedback and help shortlist top ideas to solve a problem (see OpenIdeo).

-

Innovation Labs / Accelerators / Incubators: Programmes designed to support entrepreneurs or teams develop their early-stage ideas into fully-fledged products and services that can solve problems. The support offered can include mentorship, money, co-working facilities, training, and access to potential partners and investors (see Bethnal Green Ventures or UNICEF Innovation Labs).

These approaches are not mutually exclusive, nor are they the only ones available. You can launch a funding call through a workshop or have the top ideas coming out of a crowdsourcing challenge attend an accelerator programme. The important thing is to choose an approach that matches the problem that you want to focus on.

Choosing an Incentivisation Approach

How do you know which approach to use and when?

In our previous post we outlined three roles a funding organisation can play – help build a community of solvers, expand it by bringing in new people and ideas, or support it by giving solvers relevant resources. Each of these roles will require a different incentivisation approach.

Here’s our interpretation of how the above incentivisation approaches map onto these three roles:

-

If a funder is looking to build a community of solvers, then workshops, hackathons, or crowdsourcing platforms can be relevant approaches. Although different in form and structure, these approaches are useful at drawing attention to little known problems or significant emerging ones, encouraging conversations around them and motivating people to work on solutions.

-

If the aim is to expand a community of solvers, funders can explore the possibility of setting up challenge prizes, sandpits, workshops, or make use of crowdsourcing platforms. Core to these approaches is encouraging collaborations between people or teams with different backgrounds and skills. Their aim is to bring on board new perspectives or domains of expertise that can challenge held expectations and provoke new ways of thinking.

-

If a funder is looking to support a community of solvers, approaches like funding calls, innovation labs, incubators or accelerators can help them achieve this goal. These approaches focus on offering wide ranging support to problem-solvers such as funding, mentorship, access to facilities, users and investors, as well as partnerships or contracts.

Having a rough idea of what your funding organisation needs to incentivise – whether it’s building, expanding, or supporting a community of solvers – represents an important starting point to designing an approach that can have a genuine impact.

It’s also useful to know that the boundaries between these approaches are very loose. It is often the case that in the process of ‘choosing’ a suitable approach you end up creating a new format – one that is tailored to the problem and its solvers.

Adapting the Approach

Any incentivisation approach you choose will need to be adapted. This is where knowledge about the problem and the community of solvers comes in.

The motivations of solvers, their available resources and the level of risk they’re willing to take should all shape the approach.

For example, if you’re designing a challenge prize, this information can help you define the criteria for a winning solution or the size of the reward. If you’re designing a crowdsourcing call, it can help you understand how to best articulate the problem to ensure a broad reach and diverse response. For a workshop, it can help you define the goals of the event and identify key attendees who need to be part of the conversation.

Each incentivisation approach will have its own defining features. The design of these features should reflect the problem, as well as the needs of its solvers.

In the end, an incentivisation approach is not just a way of flagging up a problem that needs to be solved. It’s about creating an engaged and adequately resourced community around that problem.

Refining the Approach

After creating an initial version of the approach, it’s time to test it with potential solvers. The aim of this step is to find out whether the approach is appealing, supportive and relevant.

-

Appealing: Is the approach engaging and motivating? Is it likely to attract the people and collaborations needed to build impactful solutions?

-

Supportive: Does it offer problem-solvers the necessary support to start developing impactful solutions? Is it inclusive and accessible to those who could add value to this process?

-

Relevant: Will this approach and the resulting ideas actually help solve the problem?

A quick way to figure out the above is to ask likely participants: ‘Would you take part in this?’. If the answer is ‘No’, understand why not and keep iterating the approach until the answer is ‘Yes! Where do I sign up?’.

Closing note: Designing for Impact

Measuring and demonstrating the impact of a funding programme is never going to be an easy or clear cut process. But being open, transparent and deliberate about the process of designing such a programme can help maximise its potential for impact. To support this claim, we highlighted three areas where funders should focus their efforts:

-

Identify a good problem. Focus on problems that are real, worthwhile, timely, engaging and suitable for your organisation to prioritise.

-

Understand the skills and collaborations needed to come up with constructive ideas. Understand who are the people and communities able to work on solutions, what motivates them and what might limit their involvement. This will help you define your role in this process – are you building, expanding or supporting a community of solvers?

-

Design an incentivisation approach that motivates and supports people to build solutions. This is not just about choosing an approach that best meets a set of criteria, but about building an environment where people can think in different ways and explore new ideas and collaborations.

We introduced the above as three separate phases. In practice, they’re most likely to occur in parallel and shape and inform each other. For instance, it’s not unusual to have clients ask us to find good problems that can be solved through a specific incentivisation approach or in a given timeframe. ‘The problem’ may not always be the starting point for the design of funding programme, but it is a core component.

The aim of this series is to encourage funding organisations to design programmes that address real problems and actively engage with solvers as part of this process. Organisations able to deliver such considerate funding programmes are not only improving the likelihood of getting problems solved, but they are also creating a community of solvers who are motivated, engaged and feel part of a valuable and impactful process.

This blog post is part of a series on our Good Problems team. Each post looks at a different step in the process of designing a funding programme and makes suggestions about how to optimise to achieve a greater impact.

What are the skills and resources a community of solvers needs to build solutions to a good problem?

After identifying a good problem it’s natural to start thinking about how to solve it. Or in the case of a funding organisation, how to incentivise the right people to solve it.

The first step is to understand the skills, resources, and collaborations needed to solve a problem. This takes time and consideration. It’s not only important to understand the needs of those already working on the problem (or closely related problems), but also to understand how new sets of skills, ideas, and perspectives could be brought together to create new solutions.

In this post we talk through some of the tools that help us make sense of a community of solvers, from identifying relevant skills and resources, to understanding blockers, motivators, and risks.

Identifying Solvers

By ‘solver’ we mean anyone who is currently working or could be working on building solutions to a problem. To identify them, we start by asking what makes a good community of solvers, rather than who they are:

- What are the skills and experiences needed to solve the problem? What domain-specific expertise is needed? What other skills or perspectives would be useful?

- What kind of resources and/or facilities are needed to solve the problem? Is a lab or special equipment needed or can solutions be prototyped more simply?

Emphasizing the skills or perspectives required to come up with impactful solutions is important because people rarely identify with a problem if it’s outside of their line of work or interest. But there are many problems that would benefit from an outsider’s perspective. An example of this is our work with the Humanitarian Innovation Fund (the HIF) around gender-based violence (GBV) prevention in humanitarian emergencies.

The HIF were looking to raise awareness of problems in the area of GBV prevention by communicating them as challenges to be solved. They were specifically interested in engaging a broader community of solvers, beyond GBV practitioners. To encourage collaborations, at the end of each designed challenge, we highlighted different skills and perspectives that would be valuable when developing solutions. Depending on the challenge, required skills ranged from tech development and user experience design, to organisational psychology, behaviour change, or advocacy. All of these are areas that are not directly associated with GBV prevention, but that could provide valuable insights and suggestions on how to develop impactful and engaging programmes. More on this project here.

After we answer the what question, we focus on the who. The aim is to start identifying individuals, teams, or communities that match the skills, perspectives, and resources needed to come up with valuable ideas. The initial research into identifying a good problem should have already generated a long-list of people working on solutions or developing new approaches.

Understanding Blockers, Motivators, and Risks

As part of the process of understanding a community of solvers, we try to grasp three things – what’s holding back progress, what would motivate potential solvers, and whether there’s any risk involved for them.

Blockers – what’s holding back progress or preventing the development of solutions? We have narrowed it down to three main causes:

- Lack of awareness of a problem: Either the problem is a newly defined one or it hasn’t been given enough attention. Focusing on the problem will not only help raise awareness, but will also legitimise the work of those trying to develop solutions.

- Lack of fresh ideas: There is a need for new thinking or collaborations to help generate innovative solutions.

- Lack of resources: Solvers may need anything from money, to facilities, connections, training, access to users, markets, or investors in order to develop their ideas.

Motivators – what drives solvers to work on solutions? These may include a combination of the following:

- Curiosity: An internal drive to solve a problem that is difficult or that no one has ever solved before.

- Recognition: A desire for an external acknowledgement of an achievement.

- Altruism: A desire to have a positive impact on society or the environment.

- Self-preservation: A drive to solve a problem that affects the solver personally.

- Financial reward: An opportunity to be first-to-market, form a partnership, or claim a prize.

Risks – are there any risks problem solvers could be exposing themselves to by working on solutions? Some of these may include:

- Wasted time: Time spent developing a solution may be better spent working on other projects.

- Financial risk: Money or other resources required to build a solution could be used to develop other projects.

- Loss of competitive advantage: Developing solutions as part of a specific funding programme could impact on a team’s competitive advantage. For example, taking part in a challenge prize could require solvers to share details about the solution they’re working on with judges or the wider public. This may jeopardise their first-mover advantage and expose their solution to the market earlier than originally intended.

From Understanding to Incentivising

In the process of designing an impactful funding programme, understanding the community of solvers plays a dual role. It helps ensure that the people, collaborations, and communities who are most likely to come up with valuable ideas are correctly identified, and it provides important insights into how to motivate and support them along the way.

In addition to this, focusing on solvers helps funders develop a more nuanced understanding of their own role as part of the problem solving process. Depending on the type of problem and maturity of the community of solvers, the role of a funding programme may be to:

-

Build a community – Raise awareness of the problem and create a community of solvers that are motivated, well resourced, and recognised as working on a worthwhile problem.

-

Expand a community – Engage new people with different skills and perspectives, nurture opportunities for collaboration and/or constructive competition, and encourage idea exchange.

-

Support a community – Supply the community of solvers with relevant resources such as funding, access to facilities and equipment, feedback from mentors, users, industry, or investors.

These categories are not only useful in helping funders define their objectives and priorities, but they provide a framework for thinking about different approaches to incentivise problem solving.

In the last post of the series, we will take a closer look at existing incentivisation approaches, from allocating grants to launching challenge prizes, and we share some of the things we’ve learned about designing approaches that both motivate and support a community to solve a good problem.