This blog post is part of a series on our Good Problems team. Each post looks at a different step in the process of designing a funding programme and makes suggestions about how to optimise to achieve a greater impact.

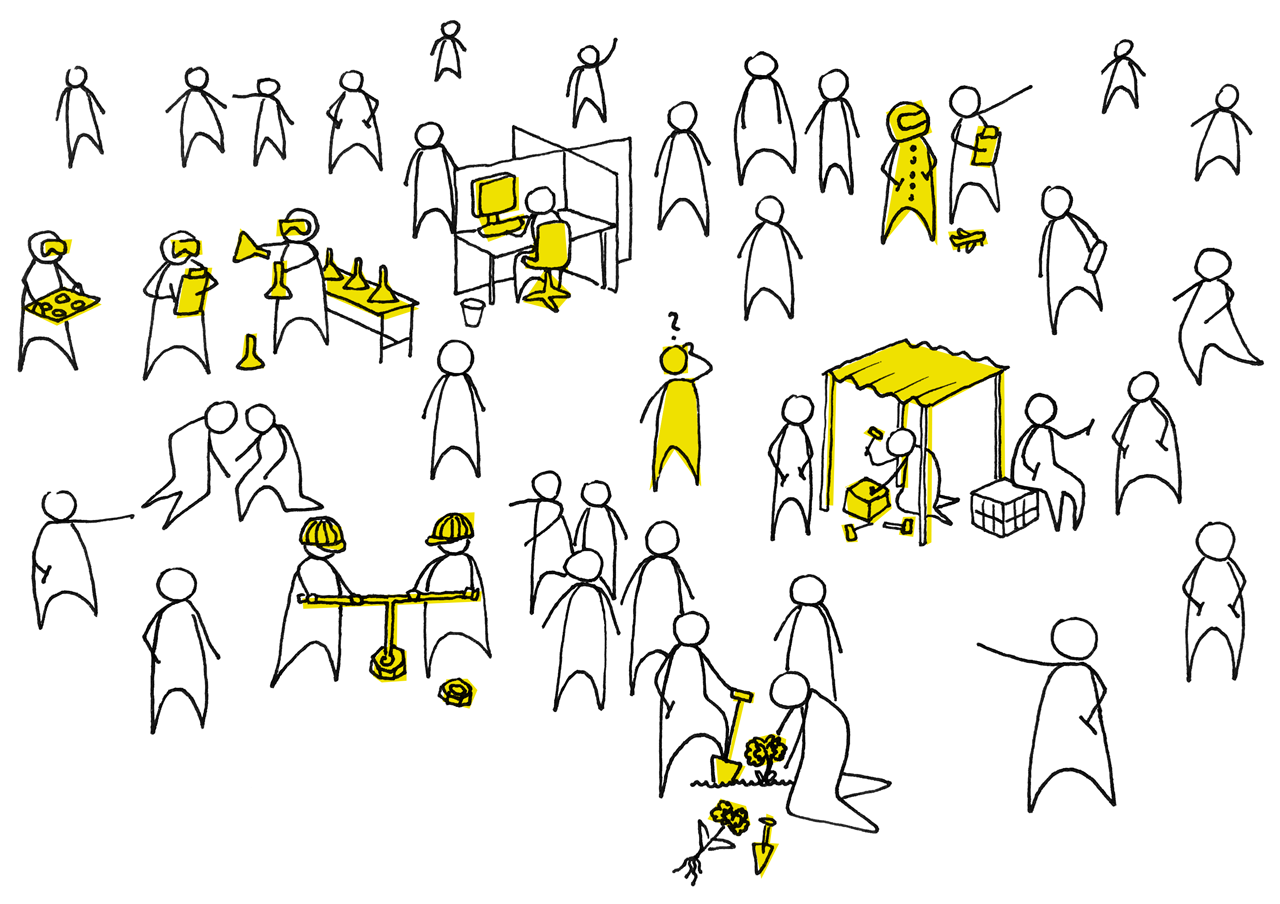

What are the skills and resources a community of solvers needs to build solutions to a good problem?

After identifying a good problem it’s natural to start thinking about how to solve it. Or in the case of a funding organisation, how to incentivise the right people to solve it.

The first step is to understand the skills, resources, and collaborations needed to solve a problem. This takes time and consideration. It’s not only important to understand the needs of those already working on the problem (or closely related problems), but also to understand how new sets of skills, ideas, and perspectives could be brought together to create new solutions.

In this post we talk through some of the tools that help us make sense of a community of solvers, from identifying relevant skills and resources, to understanding blockers, motivators, and risks.

Identifying Solvers

By ‘solver’ we mean anyone who is currently working or could be working on building solutions to a problem. To identify them, we start by asking what makes a good community of solvers, rather than who they are:

- What are the skills and experiences needed to solve the problem? What domain-specific expertise is needed? What other skills or perspectives would be useful?

- What kind of resources and/or facilities are needed to solve the problem? Is a lab or special equipment needed or can solutions be prototyped more simply?

Emphasizing the skills or perspectives required to come up with impactful solutions is important because people rarely identify with a problem if it’s outside of their line of work or interest. But there are many problems that would benefit from an outsider’s perspective. An example of this is our work with the Humanitarian Innovation Fund (the HIF) around gender-based violence (GBV) prevention in humanitarian emergencies.

The HIF were looking to raise awareness of problems in the area of GBV prevention by communicating them as challenges to be solved. They were specifically interested in engaging a broader community of solvers, beyond GBV practitioners. To encourage collaborations, at the end of each designed challenge, we highlighted different skills and perspectives that would be valuable when developing solutions. Depending on the challenge, required skills ranged from tech development and user experience design, to organisational psychology, behaviour change, or advocacy. All of these are areas that are not directly associated with GBV prevention, but that could provide valuable insights and suggestions on how to develop impactful and engaging programmes. More on this project here.

After we answer the what question, we focus on the who. The aim is to start identifying individuals, teams, or communities that match the skills, perspectives, and resources needed to come up with valuable ideas. The initial research into identifying a good problem should have already generated a long-list of people working on solutions or developing new approaches.

Understanding Blockers, Motivators, and Risks

As part of the process of understanding a community of solvers, we try to grasp three things – what’s holding back progress, what would motivate potential solvers, and whether there’s any risk involved for them.

Blockers – what’s holding back progress or preventing the development of solutions? We have narrowed it down to three main causes:

- Lack of awareness of a problem: Either the problem is a newly defined one or it hasn’t been given enough attention. Focusing on the problem will not only help raise awareness, but will also legitimise the work of those trying to develop solutions.

- Lack of fresh ideas: There is a need for new thinking or collaborations to help generate innovative solutions.

- Lack of resources: Solvers may need anything from money, to facilities, connections, training, access to users, markets, or investors in order to develop their ideas.

Motivators – what drives solvers to work on solutions? These may include a combination of the following:

- Curiosity: An internal drive to solve a problem that is difficult or that no one has ever solved before.

- Recognition: A desire for an external acknowledgement of an achievement.

- Altruism: A desire to have a positive impact on society or the environment.

- Self-preservation: A drive to solve a problem that affects the solver personally.

- Financial reward: An opportunity to be first-to-market, form a partnership, or claim a prize.

Risks – are there any risks problem solvers could be exposing themselves to by working on solutions? Some of these may include:

- Wasted time: Time spent developing a solution may be better spent working on other projects.

- Financial risk: Money or other resources required to build a solution could be used to develop other projects.

- Loss of competitive advantage: Developing solutions as part of a specific funding programme could impact on a team’s competitive advantage. For example, taking part in a challenge prize could require solvers to share details about the solution they’re working on with judges or the wider public. This may jeopardise their first-mover advantage and expose their solution to the market earlier than originally intended.

From Understanding to Incentivising

In the process of designing an impactful funding programme, understanding the community of solvers plays a dual role. It helps ensure that the people, collaborations, and communities who are most likely to come up with valuable ideas are correctly identified, and it provides important insights into how to motivate and support them along the way.

In addition to this, focusing on solvers helps funders develop a more nuanced understanding of their own role as part of the problem solving process. Depending on the type of problem and maturity of the community of solvers, the role of a funding programme may be to:

-

Build a community – Raise awareness of the problem and create a community of solvers that are motivated, well resourced, and recognised as working on a worthwhile problem.

-

Expand a community – Engage new people with different skills and perspectives, nurture opportunities for collaboration and/or constructive competition, and encourage idea exchange.

-

Support a community – Supply the community of solvers with relevant resources such as funding, access to facilities and equipment, feedback from mentors, users, industry, or investors.

These categories are not only useful in helping funders define their objectives and priorities, but they provide a framework for thinking about different approaches to incentivise problem solving.

In the last post of the series, we will take a closer look at existing incentivisation approaches, from allocating grants to launching challenge prizes, and we share some of the things we’ve learned about designing approaches that both motivate and support a community to solve a good problem.